Climate change is an issue of economic transformation. As societies decarbonize, the focus of economic activity will shift from greenhouse gas-intensive industries to clean alternatives. As they are forced to manage intensifying environmental disruptions, industries dependent upon stable climatic conditions may rapidly decline.

While we understand what these transformations will look like in broad strokes, at a more granular level, they are marked by great uncertainty. We don’t know precisely where and at what pace decarbonization will occur. The coal industry in one country may, for example, prove to be more resilient than the coal industry in another. Rapid technological breakthroughs in the clean energy industry may render fossil fuels obsolete faster than once thought. When it comes to the physical effects of climate change, we can confidently project what things will look like at a global scale. But what those global trends mean for a particular industry in a specific community at a certain time is much less clear.

In a new article, “Identity, Industry, and Perceptions of Climate Futures,” I argue that race shapes how people understand the viability of industries and their own economic security in an era of climate dislocation. I show that the racial makeup of industry workforces affects which industries Americans think are likely to survive, and which are not. When an industry features more workers from a racial group that people see as politically privileged, people become more confident in that industry’s access to government support and, in turn, its ability to withstand future threats from decarbonization and climate change.

Climate Risk and Uncertainty

I distinguish between two types of climate-related risks in this study. Climate-forcing industries — think oil and heavy manufacturing — face “transition risks” as governments tighten regulations on carbon emissions and societies replace fossil fuels with renewables. Climate-vulnerable industries face “physical risks” from climate impacts like drought, floods, and rising sea levels.

Both types of risk are characterized by great uncertainty. While governments can prop up struggling industries with subsidies, their ability to do so is constrained by budgets and the nature of the climate challenge. Protecting climate-forcing sectors, enabling them to continue to emit planet-warming gases, imperils climate-vulnerable industries. Decarbonizing to protect climate-vulnerable sectors, by contrast, exacerbates risks to climate-forcing industries.

Citizens thus must judge which industries are more likely to enjoy government backstops. My study shows that these evaluations depend, at least in part, on the demographic makeup of workforces and citizens’ beliefs about racial favoritism in government.

The Role of Race

Americans often have strong — and discordant — beliefs about which racial groups are privileged by the government. Many consider white Americans to be favored by government policy and Black Americans to be disadvantaged. Many others report the opposite, believing that minority communities enjoy unfair advantages in society (recent controversy over affirmative action is a good illustration of this).

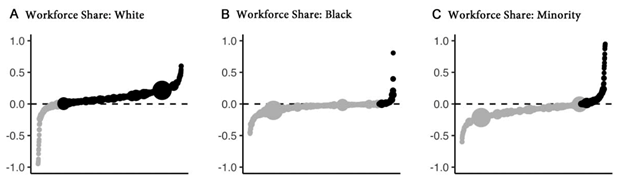

Beliefs about racial hierarchies introduce stark differences into how Americans think about climate futures. They do so because the racial makeup of industries exposed to climate-related risks varies widely. Climate-forcing sectors tend to be disproportionately white (see Figure 1). In 2019, 83% of U.S. counties featured climate-forcing industries that were whiter than the surrounding community; in Texas, the climate-forcing workforce was about ten points whiter than the state’s overall workforce. On the other hand, climate-vulnerable industries are far likelier to be disproportionately non-white; California’s climate-vulnerable workforce (largely based in agriculture) is ten points less white than the rest of the state.

Figure 1: Shares of climate-forcing workforces by race, relative to the racial makeup of a county. Each dot represents one county, scaled to the number of workers in each county. Dots colored black indicate that a county’s climate-forcing workforce features a disproportionately large share of workers from a particular racial group.

I argue that among Americans who believe white citizens are favored by government, the whiteness of climate-forcing industries should be seen as a shield against decarbonization, supporting their continued survival even as pressure from cleaner competitors mounts. For those who hold the opposite view, however, that whiteness may instead be seen as a burden, with the government likely to funnel resources towards more minority-heavy climate-vulnerable industries.

Findings and Implications

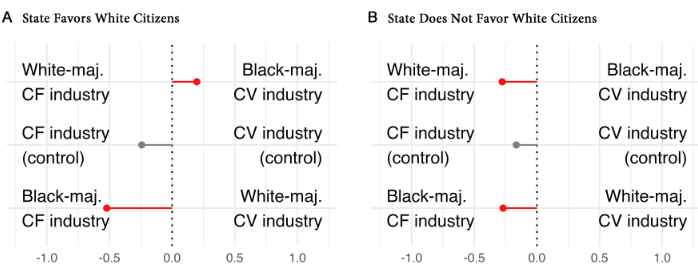

I test this argument using a survey fielded on a sample of about 1,600 American adults. I first measure how respondents understand racial hierarchies in the U.S. Close to half the sample expressed the view that the government disadvantages white Americans, and Black Americans favored. In a pair of experiments embedded in the survey, I then show respondents hypothetical climate-forcing and climate-vulnerable industries, randomly varying whether a given industry is majority white or majority Black.

When told that an industry primarily employs members of a favored group, respondents became significantly more confident in that industry’s access to government subsidies and more sanguine about the industry’s future risk of decline. Respondents also became more confident in the security of workers in the industry, indicating that they are more likely to enjoy government employment protections and better able to obtain assistance from elected representatives.

Notably, these results transcend traditional cleavages in American politics. Democrats and Republicans, Biden and Trump supporters, and wealthier and poorer Americans all respond to these cues in similar ways.

These results suggest that racial divides may influence how communities politically mobilize on climate issues. For example, they indicate that fears of status threat and upturned racial hierarchies among some white Americans may increase mobilization against decarbonization. White communities worried about their place in society may aggressively press for assistance for local climate-forcing industries, not confident that the government would act otherwise.

The results also suggest that race may affect public support for initiatives to gradually phase out climate-forcing industries (“just transitions”) and relocate climate-vulnerable communities (“managed retreats”). Stakeholders who believe themselves to be part of a privileged group may resist such transitions, instead gambling that the government will come to their aid if needed in the future.

Noah Zucker is an Assistant Professor of Politics at Princeton University. His work focuses on the political economy of climate change and has appeared in the American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, and World Politics.

What a thought-provoking read — your article “How Race Shapes Climate Attitudes” really highlights the complex ways race, identity, and environmental views interplay. Thanks for sharing this insightful piece!