Imagine you’re a politician enjoying a decent run in the opinion polls. You post on Facebook about the issues you care about most—your party’s core themes, the things you think will win you votes in the long run. Then one morning, a new poll drops: your party has lost ground. Suddenly, the political weather feels colder. What do you do?

Our research shows that many politicians in this situation change tack—fast.

The Problem of Bad Polls

Polls are more than just numbers; they’re a political weather forecast. When results show a drop in voter support, it’s a warning signal that you might be drifting out of step with public concerns. For a politician, that’s dangerous territory. Losing touch with voters can mean losing your seat.

But how do politicians decide what to talk about when the pressure is on? They don’t have a direct line to every voter’s mind, so they look for signals—and one of the clearest signals is the news.

Turning to the Media Agenda

The media plays a powerful role in shaping public opinion. The issues dominating front pages and news broadcasts often mirror the public’s main concerns. When the polls go south, politicians seem to pay closer attention to these “top of the news” topics—and bring them into their own Facebook updates.

In our study of over 27,000 Facebook posts by 146 Danish members of parliament, we tracked what politicians were talking about week by week during the year 2016-2017. We matched their posts to the five issues most covered in major Danish newspapers at the same time.

The pattern was clear: when a party’s poll numbers dropped, its politicians were about 17% more likely to post about those top media issues in the following weeks.

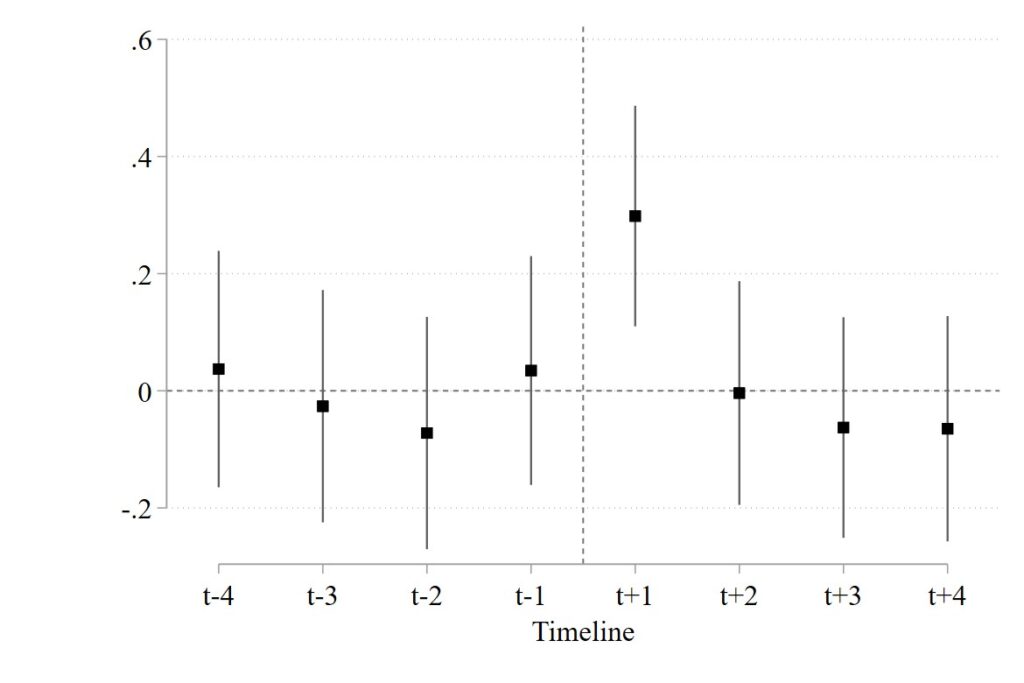

Figure 1 shows this relationship clearly:

When polls fall – marked by the vertical line on the horizontal timeline – the share of Facebook posts covering top media issues rises immediately (measured on the vertical axis). The jump in the marker after the vertical line means that losing politicians are following the media agenda more closely after bad poll results compared to winning politicians. (Technical note: the Figure shows the differences in trends, i.e., in the average number of matches between the issue content of Facebook posts and top five media stories for the politicians experiencing a poll drop in the treatment group vs politicians experiencing a poll improvement or an unchanged poll in each of the four weeks before and after the poll.)

Facebook: Fast, Flexible, and Public

Why Facebook? Because it’s a low-cost, high-visibility platform. Unlike TV appearances or official speeches, it doesn’t require approval from party leadership or the media. Politicians can post instantly, directly addressing both their followers and, indirectly, the wider public.

That makes it the perfect tool for a quick image adjustment—showing voters, “I hear you, I’m talking about what matters to you right now.”

Not Just a Personal Panic

We thought the most insecure MPs—those with the slimmest margins at the last election—might react more strongly to bad polls. Surprisingly, they didn’t. The shift towards media-driven topics wasn’t a solo survival strategy; it was a herd moving. Politicians from the same party seemed to move alike when the polls turned bad, regardless of how personally vulnerable they were.

Even more surprisingly, they didn’t just focus on issues in the news where the party traditionally has a strong competence reputation in the eyes of the voters. Instead, they often talked about their rivals’ signature issues in the news—perhaps an attempt to compete directly for attention and credibility.

Why This Matters

This behavior shows the fast-moving, tactical side of modern politics. Social media doesn’t just let politicians set their own agenda—it also gives them a quick way to follow the public’s concerns, especially when they’re under pressure.

For voters, this means the issues you see politicians talking about online may not always be long-term priorities—they might be rapid responses to the latest opinion polls and headlines.

For researchers, it’s a reminder that the line between “leading” and “following” the public agenda is thin. When the polls drop, even confident leaders can become followers. Previous research suggests that politicians are either ‘leaders’ or ‘followers’; however, we find that the answers depend on the quality of the polls. Losers tune in on the voters, winners stay on their preferred issues even if they are not in the news.

The Bigger Picture

We studied a year without an election campaign, so these shifts happened during “normal” politics. If anything, the effect could be even stronger during an election, when every poll feels like a make-or-break moment.

Social media has changed the rules of political communication, but one rule still applies: in politics, when you’re losing, you listen harder. And on Facebook, that listening shows up fast.

Authors

Helene Helboe Pedersen is a professor of political science at Aarhus University. Her main research interest is political representation, and she has studied political representation via interest groups and political parties, from the perspective of voters as well as elites, and using qualitative as well as quantitative data. Her recent work on political representation appears in the European Journal of Political Research, Party Politics, and Democratization.

Henrik Bech Seeberg is a professor of political science at Aarhus University. His main research interests are politicians’ information processing and filtering, and political parties’ competition to decide which policy issues top the political and public agenda. He currently leads a research project on youth representation and political parties’ youth wings.

This is a fascinating look at how politicians adapt their online communication based on polling data. The focus on Facebook posts and the connection to media agendas makes a lot of sense in today’s political landscape.

The finding that Danish MPs were 17% more likely to discuss top media issues after a poll decline is compelling. It raises an interesting question about authenticity. While it’s strategically savvy to address concerns heightened in the media, does this perceived shift jeopardize a politician’s credibility in the long run? Do followers perceive this adaptation as genuine responsiveness, or as calculated pandering? I’d be curious to know if subsequent research explored how voters themselves perceive these shifts in messaging after a dip in the polls. Perhaps sentiment analysis could add another layer to this research and show, not just *what* politicians are posting about, but how it’s received. Thanks for sharing this insightful study!