Online Framings of Offline Violence in Syria’s Civil War

How do representations of violent conflict differ across social media platforms? Our recently published article tackles this question through a close study of how Syrian users post across three broadly used platforms: Facebook, Twitter, and Telegram. By taking a broad lens to describing differences across these platforms, our work underscores that individuals who use different platforms – or researchers who study them – are presented with broadly different understandings of the causes and consequences of ongoing conflicts.

Bringing Conflict Narratives Online

Scholars often note that any violence provokes a secondary conflict to define its meaning. By embedding ongoing violence within broader narratives, elite and meso-level actors can influence individuals’ support for conflict escalation or termination or domestic and international actors’ willingness to intervene. While these narrative contests increasingly occur online, few studies have examined how or why they differ across the proliferating social media platforms used in conflict environments.

We point to twin drivers of narrative differences offline, point to both the audiences users reach on different platforms as well as the technical affordances these platforms facilitate. While actors often broadly diversify their narratives to reach multiple audiences, our study primarily differentiates between the domestic audiences who experience day-to-day violence, and the more distant, international audiences whose interventions can reshape the trajectory of conflict. On social media, users reaching these audiences also consider platforms’ differing technical affordances, which can include features like post length, the ability to use pseudonyms, and policies around content filtering and graphic images. Jointly, these audiences and technical affordances can generate broadly different presentations of the same conflict in different online environments.

Studying Narratives in Syria’s Civil War

We examine how these twin processes influence aggregate presentations of violence among Syrian users on Facebook, Twitter, and Telegram. To do so, we used parallel processes to identify conversations in Arabic among meso- and elite-level who posted millions of text-based messages and images during a period when the conflict’s frontlines were relatively static, from the U.S. backed and Kurdish led Syrian Democratic Forces defeat of the Islamic State in Raqqa in October 2017 through December 2020. We supplement our findings from a more tightly paired comparison of 124 users who simultaneously post across all three platforms. To analyze these messages, we used tools like structural topic models, word embeddings, and image analysis via convolutional neural networks. Finally, we sent a structured questionnaire to a subset of users in our analysis, asking them to explain in their own words which platforms they use and why.

Local Violence, Global Framings

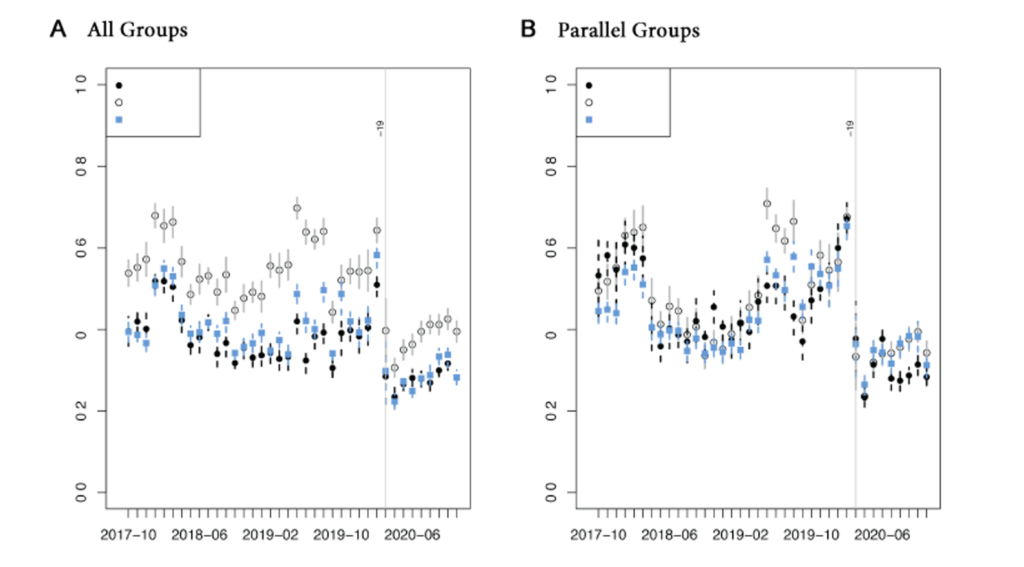

Our results underscore that discussions of violence and its impacts remained central across platforms (Fig 1, Panel A) while pointing to the distinctive ways that individuals use these platforms in the Syrian conflict. Linking to a wide set of scholarship on the Syrian conflict, we analyzed messages in terms of their relationship to the conflict’s macro-narrative competition, between a pro-opposition narrative centered on Syrians’ struggle for freedom from Bashar Al Assad’s authoritarian violence and a loyalist, pro-Al Assad narrative framing the opposition as tools of a foreign-backed conspiracy or as sectarian. A more micro-level framing centers around the daily costs of conflict, the proliferation of actors to the conflict beyond this binary, and the deep suffering of all involved.

These narratives were well represented online in the period we studied. Across text and images, we show that narratives on Twitter centered more directly on the conflict’s macro-level cleavages, while on Telegram they captured a more local story, divorced from macro-level meaning, and often with more emphasis on the conflict’s evolution and the proliferation of conflict actors. We found that Facebook fit somewhere in between, with more quotidian conversation heavily featuring loyalist narratives.

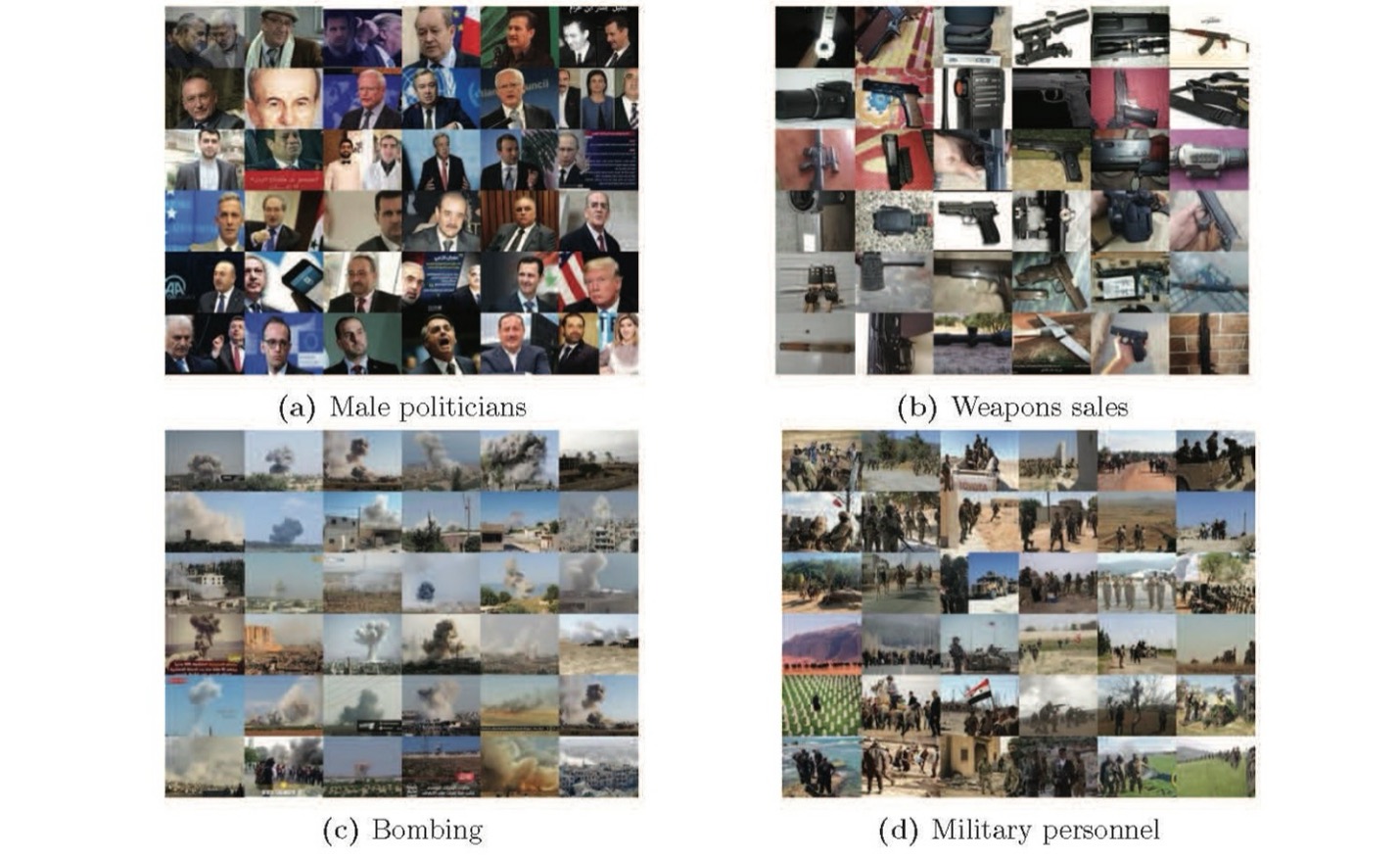

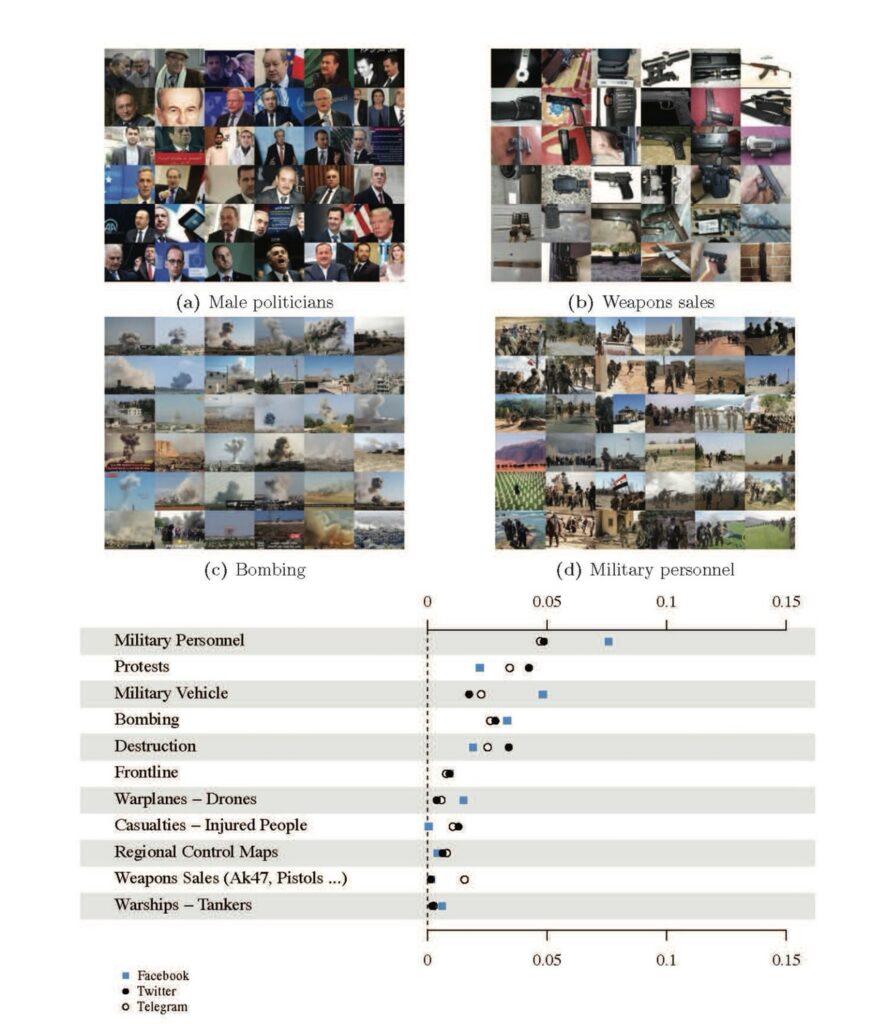

Figure 2 explores these differences using the computation analysis of images. While on Facebook we see more staged photos of military personnel and vehicles, Twitter more prominently features non-violent protests, and Telegram emphasizes more open destruction and even the growing role of the illicit black market in weapon sales.

These differences across users are apparent even when examining speech from users posting on all three platforms. For instance, Figure 3 shows a set of posts from the same media collective on the same day, which differentially eulogizes a youth killed by Assad’s forces in 2011 on Twitter (Panel A), news about airstrikes and Assad-Islamic State conflict on Telegram (Panel B), and news about both, in different form, on Facebook (Panel C).

We link these differences to the audiences and affordances on these platforms. On Twitter, a Syrian photographer described an effort to reach “the whole world, in the hope that it will one day have an impact,” whereas Telegram allowed him to “convey Syria’s bloody reality, and facts, as is” to local audiences deeply impacted by the day’s news. On Facebook, where technical affordances make it more difficult to post anonymously or under pseudonyms and with even heavier content filtering, we saw more staged images and conversations blending “global and local” accounts, in the words of one page administrator.

Implications

Our study implies that users of different platforms, and the scholars studying them, can come away with distinct understandings of the costs, causes, and evolving dynamics of conflict. While relevant affordances and audiences may differ across conflicts and as platforms evolve, future scholarship should work to disentangle how audiences and technical affordances shape these differences. In the words of one Syrian journalist:

“A social media user must determine their message, and then the audience they want to deliver it to. From there, they determine the platform they’ll put it on. This platform then shapes the message. As a result, the relationship between the message, the platform, and the audience is triangular. They interact with one another, and cannot be disentangled.”

We encourage future scholarship to engage with this journalist’s challenge.

Author

Erin Walk, Elizabeth Parker-Magyar, Kiran Garimella, Ahmet Akbiyik, and Fotini Christia