In the early 1990s, the growth of independent media played a vital role in Africa’s democratic transitions. New outlets broke state monopolies, promoting accountability and pluralism. But media freedom has not been an unqualified good. In many countries, partisan actors have captured media, establishing outlets and steering revenue toward friendly coverage. Mis-, dis, and malinformation (MDM) thrives in such environments. In some cases, the media have fueled discrimination and even violence in places like Cameroon, Kenya, and Rwanda.

For some, these dangers suggest that the pendulum has swung too far toward unfettered media freedom, and that governments should step in with stronger regulations. According to Afrobarometer, the share of Africans who support media freedoms declined significantly between 2011 and 2018. Further, those who believed media freedoms were increasing were actually more likely to support restrictions than those who saw freedoms as stagnant or declining.

Of course, the picture is complicated. Attacks on media have intensified in Eswatini, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, and elsewhere. Limits can cut citizens off from essential sources of information, undermining engagement, accountability, and fair elections. Many thus see media freedom as Janus-faced: necessary for democracy, but potentially carrying the seeds of its demise.

When Do African Publics Support Media Restrictions?

Despite the stakes, we know little about how Africans form opinions on media freedom. To address this gap, I worked with a team of Afrobarometer researchers on a large-scale study in Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda, combining a phone-based conjoint survey experiment with expert interviews and focus groups.

In our experiment, subjects were presented with short descriptions of hypothetical radio stations accused of wrongdoing. Three details varied randomly:

- The accuser – the president, the opposition, or an independent agency

- The accusation – hate speech, supporting armed groups, COVID-19 misinformation, lies about candidates’ private lives, partisan bias, or failure to pay taxes.

- The station’s funding source – domestic or foreign

Subjects then chose from a range of escalating government responses, including doing nothing, issuing a warning, levying a fine, or shutting the station down, temporarily or permanently.

This design lets us measure how the identity of the accuser, the nature of the alleged harm, and the source of funding shape public support for restrictions, while avoiding some of the bias that can arise in direct questions about abstract principles like “media freedom.”

What the Results Show

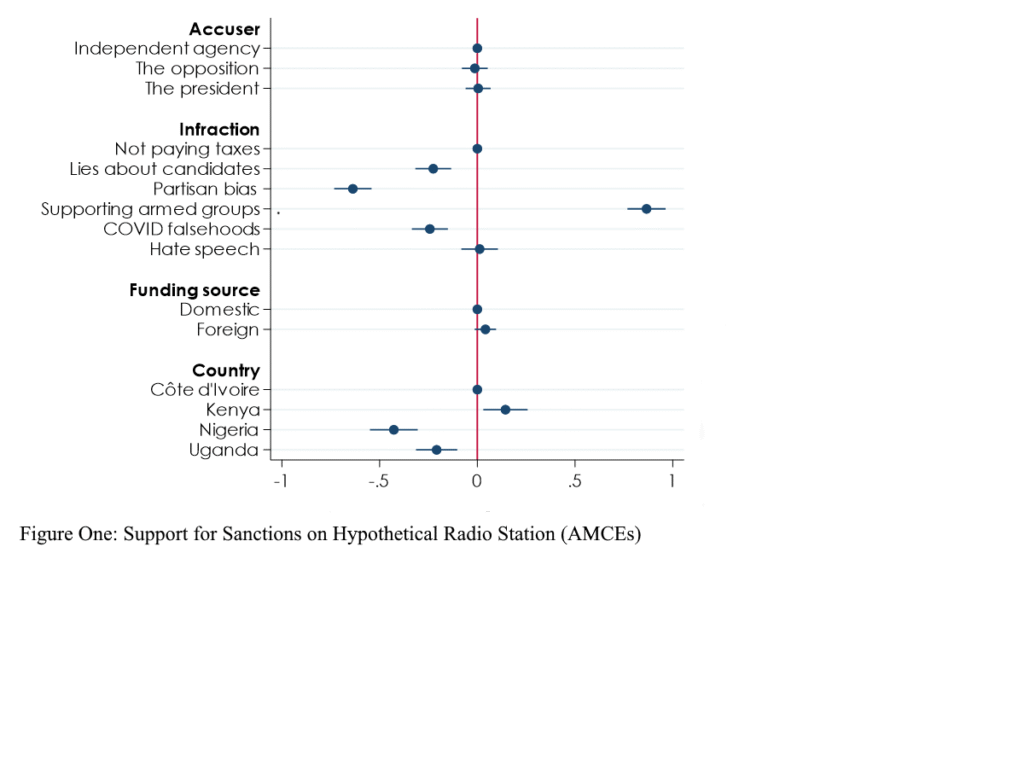

We report the estimated average marginal component effects (AMCEs) in Figure 1. Several patterns emerged:

1. Broad support for restrictions, but preferences for milder penalties

Most subjects supported action in at least one scenario. But harsher measures like permanent shutdowns were far less popular than written warnings or fines. Citizens seem willing to regulate, but with a lighter touch, usually.

2. Partisan cues matter little

We had expected responses would depend on who was making the accusation. Contrary to this, the president’s involvement in an accusation did not trigger calls for tougher restrictions, even among people who trusted him. The only consistent partisan effect was that citizens who trusted the president were less supportive of restrictions when accusations came from the opposition. Overall, support for restrictions does not appear to be driven by partisan loyalty.

3. The nature of the harm matters

Support for restrictions depended heavily on the offense. When compared to the baseline of not paying taxes, supporting armed groups drew significantly harsher responses. On the other hand, infractions like COVID-19 MDM, partisan bias, and lies about candidates were seen as significantly less deserving of harsher punishments compared to tax evasion. This suggests citizens distinguish between harms they view as direct threats to security and those they see as political or informational.

- Funding sources rarely matter.

In most countries, whether a station was domestically or foreign-funded had little effect on attitudes. The exception was Côte d’Ivoire, where foreign funding led to stronger calls for punishment. This probably stems from strong anti-French sentiments in that country’s former colonies.

Implications for Democracy & Policy

These findings suggest Africans’ attitudes toward media freedom are more context-dependent than blanket survey questions usually reveal. Willingness to restrict media depends far more on what the outlet is accused of than on who is making the accusation. This has several implications:

- Framing matters. Politicians seeking to curb freedoms may have more success if they point to security threats, rather than bias or MDM. Those seeking to fight against potentially anti-democratic moves might need to frame their counter-messaging appropriately.

- Public opinion is not purely partisan. People are not simply following the lead of their preferred political camp when it comes to media restrictions.

- Citizens may see restrictions as pro-democratic. For many, restricting media is not a betrayal of democratic values but a way to protect them. In focus groups, many directly justified certain restrictions as supporting values such as peace, fair competition, and minority rights. In fact, Afrobarometer data show that democrats in the focus countries are actually more supportive of media restrictions targeting hate speech and MDM than their less-democratic counterparts are.

Methodologically, we also push forward the study of public opinion and democratic backsliding. By varying the scenario and severity of possible responses, we offer lessons for how to study democratic attitudes. Support for institutions like media freedom is not fixed; it can shift depending on the context. Further, citizens are capable of suggesting different “punishments” for various “crimes.” Researchers relying only on general opinion questions risk missing these nuances.

A Fragile Balance

The debate over media freedom in Africa is not a simple contest between democrats and authoritarians. Many want independent media, but they also want protection from the harm that unfettered speech can bring. Balancing these priorities is difficult, and the stakes are high.

If the pendulum swings too far toward restriction, citizens lose access to information needed to hold leaders accountable. If it swings too far toward absolute freedom, harmful content can undermine trust, spread division, and even threaten lives.

The challenge for Africa’s democracies is to find the right balance between these dangers by protecting citizens from genuine threats while ensuring that regulation does not become a tool for silencing dissent. Public opinion will be a key part of that equation. Understanding the complexity of those opinions is the first step toward policies that both safeguard democracy and address its vulnerabilities.

Author

Jeffrey Conroy-Krutz is an Associate Professor at Michigan State University, where he currently serves as Chair of the Department of Political Science. His research examines political communication in Africa, with a focus on polarization, elections, and identity. He has published in the Journal of Politics, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and Comparative Politics, among others.