For decades, American voters tended to like politicians who shared their gender or race. This preference for “descriptive representation” often reflected more positive associations with members of one’s own group. But in today’s polarized era, that pattern is changing in surprising ways.

In a new study, I show that the effect of a representative’s race and gender on their constituents’ evaluations now depends on voters’ partisanship, not their own racial or gender identity. Democratic voters’ increasingly positive attitudes towards women and people of color are accompanied by shifting evaluations of representatives from these groups in the US Congress. Republicans’ attitudes about these groups have not shifted, and neither have their assessment in any consistent manner.

Descriptive Representation is No Longer Just About Ingroup Favoritism

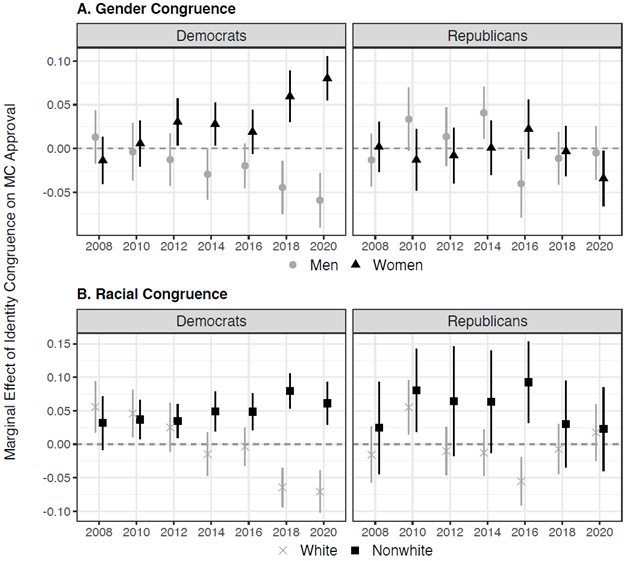

I draw on Cooperative Election Study surveys from 2008–2020 and new data on Congressmembers’ race and gender to track changes in how constituents evaluate their representatives. As shown in Figure 1, I find a striking pattern: among dominant-group Democrats (men and whites), classic ingroup favoritism has faded. In earlier years, white and male Democrats rated gender-congruent (white and male) Congressmembers more highly. But by 2016, all Democrats began to give higher ratings to women and people of color in office, regardless of whether they shared those identities.

Among Republicans, those patterns do not appear. Male and white Republicans give similar ratings to Congress members regardless of the member’s race or gender. Republican people of color are the one exception: they provide higher ratings to representatives who share their racial background.

In short, Democrats’ growing positive attitudes toward marginalized groups, especially among white and male Democrats, appear to have shifted how they evaluate Congress members.

What Does this Mean for Accountability?

This changing landscape doesn’t just matter for who receives positive ratings. It also changes how voters hold representatives accountable.

Voters typically penalize representatives who stray ideologically from their own views. But I find that Democratic voters give more leeway to women and people of color who they perceive as diverging ideologically. In other words, they are less likely to penalize a woman or a person of color in Congress for being too liberal or too conservative than they are to penalize their male and white counterparts. Republicans, by contrast, penalize ideological distance consistently, regardless of a member’s identity. They also impose larger overall penalties for ideological divergence than Democrats.

The result is two very different standards of accountability. In the Democratic Party, being a member of a minority group in Congress can buffer against ideological misalignment. Among Republican constituents, ideological misalignment is punished similarly, no matter a representative’s race.

What Explains this Shift?

Could these changes be because women and people of color in Congress are now more effective than men and whites? Or do Democratic voters now think that women and people of color are more ideologically like themselves?

If women anticipate discrimination when running for office, only the most qualified women run.

This would produce a pool of highly qualified women and a more mixed pool of men, potentially leading to greater effectiveness among women in office. More effective representatives should receive higher approval ratings. The same logic could apply to people of color.

Constituents may also perceive these members as sharing their ideological preferences. Women and people of color hold more liberal views, on average, and the Democratic party as a whole has shifted leftward. Democratic voters may therefore believe that women and people of color better represent their interests.

However, neither of these alternative explanations fits the patterns I found. Member effectiveness has not shifted in ways that would explain the change, and the gaps between men and women, or between white members and members of color, have not grown. Constituents also do not perceive greater ideological closeness to women and people of color in Congress over time.

Instead, the pattern is most consistent with broader shifts in racial and gender attitudes, particularly among Democrats. In recent years, Democrats, especially whites and men, have become more liberal in these attitudes. These growing positive feelings help explain why they are now more supportive of representatives who do not share their race or gender. Republicans, meanwhile, have not shifted in the same way, with their attitudes remaining relatively stable.

Broader Implications for Representation

Polarization has changed the logic of descriptive representation. Identity still matters, but not in the same way it once did. For many Democrats, descriptive representation of historically marginalized groups now carries symbolic value even in the absence of identity alignment. For Republicans, descriptive traits play a much smaller role in how constituents evaluate their representatives.

If voters grant politicians different forms of leeway depending on the politicians’ identities, the consequences for policymaking, accountability, and democratic legitimacy could be far-reaching.

Anna Weissman is an incoming Postdoctoral Fellow at Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Democratic Politics.