On March 7, 1965, a group of peaceful Black and white protesters were attacked by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. These protesters were demanding that the United States finally make good on the promises of the 15th Amendment and let all Americans vote, regardless of the color of their skin. The violence caused national outrage, and a few short months later, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Core to the landmark civil rights legislation was Section 5 — the “preclearance condition,” as it came to be called. Preclearance required jurisdictions with prolonged, entrenched histories of race discrimination in voting to obtain federal permission before changing their election policies. Any such changes — from statewide voter ID requirements to small-town polling place locations — would have to be submitted to the Department of Justice or the DC Circuit Court of Appeals to ensure that they would not disproportionately burden voters of color. Between 1965 and 2013, preclearance prevented thousands of discriminatory policies from taking effect.

But in 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby County v. Holder that the formula used to determine which parts of the country would be covered by preclearance was no longer valid. When the Court struck down that formula, it effectively suspended preclearance itself. Since then, no jurisdiction has been required to submit each of its proposed election policy changes for review (through a separate provision of the Voting Rights Act, some jurisdictions have had to submit a small set of proposed changes for review). The conservative majority argued that the need for preclearance had run its course and that undoing the system would not harm voters in the covered jurisdictions. The dissenters argued that this approach ignored the benefits provided by preclearance in keeping racial discrimination at bay.

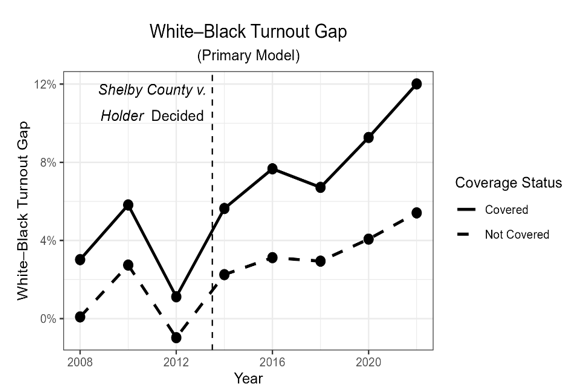

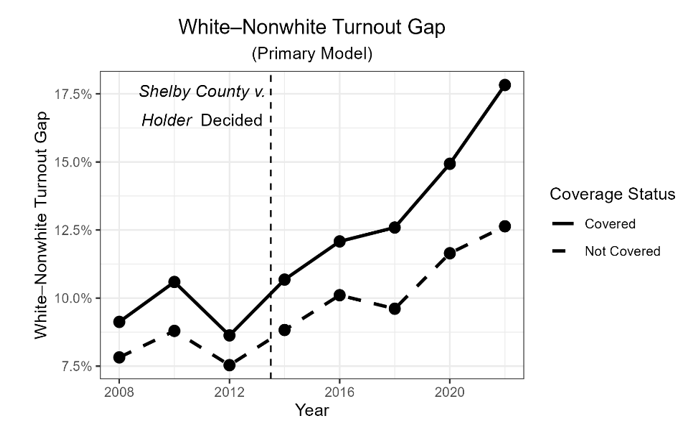

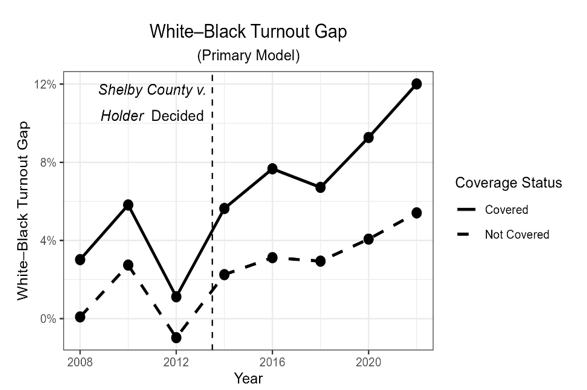

In our new paper in The Journal of Politics, we turn to the evidence to determine whether the Supreme Court majority’s prediction was correct. Using nearly a billion voter file records, we estimate the turnout rates among white, Black, and all nonwhite voters for every county in the nation between 2008 and 2022. We then compare changes in the racial turnout gap — the difference in participation between white and nonwhite voters, and between white and Black voters — in counties where preclearance had applied and in similar counties that were not covered. This approach allows us to isolate the statistical effect of Shelby County on relative turnout rates.

Unfortunately, these difference-in-differences models demonstrate just how wrong the Shelby County Court was: We find that the racial turnout gap has grown dramatically since 2012 in most of the counties covered by preclearance in 2013. While the racial turnout gap has grown everywhere, including in places not covered — a concerning trend in its own right — it grew twice as quickly on average in the formerly covered counties between 2012 and 2022. We estimate that by 2022, hundreds of thousands of ballots nationwide were never cast due to policies and practices with discriminatory effects that could potentially have been blocked by the preclearance requirement.

Figure 1a: White-Nonwhite Turnout Gap

Figure 1b: White-Black Turnout Gap

The effects of Shelby County were especially pronounced in counties where the Department of Justice had previously blocked a policy while preclearance was still in effect (that is, places that tried to adopt a discriminatory voting policy but were stopped) and in counties where Republican voters predominate. The effects were less pronounced, on the other hand, in large urban counties such as Harris County, Texas, where local election administrators have worked hard to keep voting accessible — and sometimes despite lawsuits by their state for doing so.

This fall, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the redistricting case Louisiana v. Callais. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act — the law’s remaining pillar, after Shelby County suspended Section 5 — is at risk in this case. Our new research paints a bleak reality: The last time the Supreme Court struck down a major part of the Voting Rights Act, it expanded the racial turnout gap and led to worse opportunities for Americans of color.

Kevin T Morris and Michael G Miller