Montevideo’s Lottery for Good Taxpayers

In 2004, Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, launched a pioneering program to reward punctual taxpayers by entering them into a lottery. The winners got a “tax holiday”: a full year without paying their municipal taxes.

The idea was simple. Instead of threatening late payers with penalties, why not reward the good ones? After the country’s worst economic crisis in decades, city leaders hoped this positive approach would boost compliance and, ultimately, revenue.

It didn’t work out that way.

The Montevideo lottery covered four major taxes: property, vehicle, sewage, and a “head” tax. Eligible taxpayers—those fully up to date—were automatically entered. Winners were drawn at random, using Uruguay’s national lottery system, and notified by letter to claim their prize.

We had a unique opportunity to measure the effects. Because winners were chosen randomly, we could compare their future behavior to that of eligible non-winners. We also ran field and survey experiments to see whether simply knowing about the lottery changed taxpayers’ intentions or attitudes.

The Surprise: Tax Holiday Winners Became Worse Taxpayers

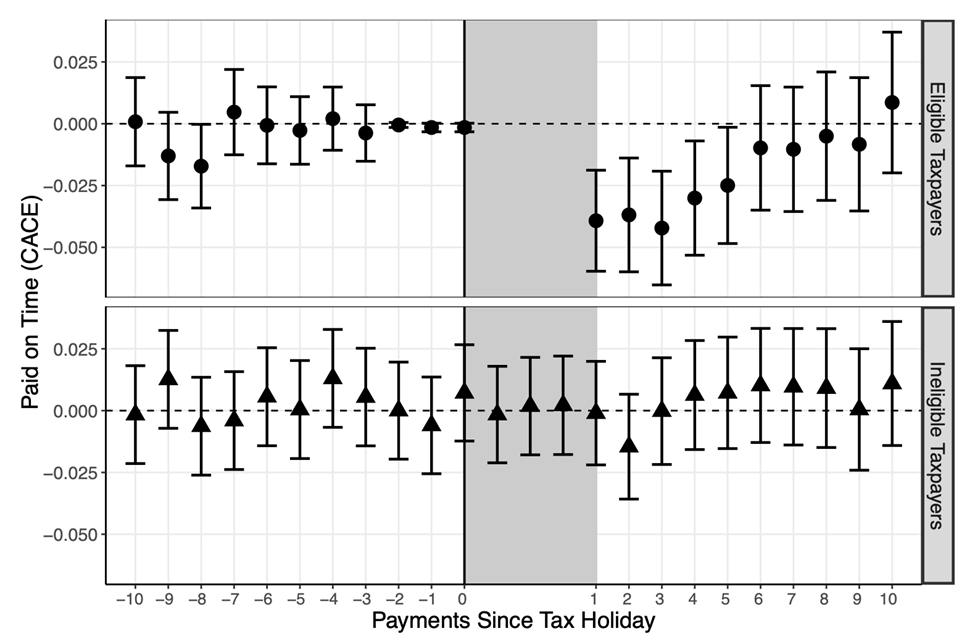

Instead of making people better taxpayers, the tax holiday made them worse. Winners were significantly less likely to pay on time for up to two years after their holiday ended. On average, compliance fell by 3–4 percentage points among winners compared to non-winners—despite both groups having perfect payment histories before the lottery.

And telling people about the lottery without giving them a holiday? That didn’t boost payment either. Whether we mailed flyers to eligible or ineligible taxpayers, the extra information had no meaningful effect on their behavior.

The figure compares on-time payment rates for eligible taxpayers who won a one-year tax holiday with those who did not (top panel). The shaded area marks the year winners were exempt from payment. Dots indicate the estimated difference in on-time payments between the two groups, with vertical lines showing confidence intervals. Before the holiday, both groups paid at similar rates. After it ended, winners were less likely to pay on time for nearly two years. No comparable difference appears among taxpayers who were ineligible for the lottery (bottom panel).

Why Did It Backfire? The Power of Habit

Our evidence points to a simple but powerful explanation: the policy broke people’s payment habits. For many in Montevideo, paying taxes meant getting a bill in the mail and walking to a kiosk to pay. Doing that over and over made it automatic—a year without paying disrupted that cycle.

We saw no drop in compliance among:

- Automatic payers, whose bank debits continued without effort.

- Vehicle tax winners, who still had to make small payments even during their “holiday.”

- Taxpayers with a long history of punctuality bounced back faster than those with spottier records.

The negative effect only appeared when the act of paying was truly interrupted.

Designing Rewards That Work

Montevideo’s well-meaning experiment ended up shrinking its tax base. After we shared the results of our study with city officials, Montevideo replaced tax holidays with one-time rebates that don’t interrupt payment routines.

The lesson is broader: habits—good and bad—play a quiet but crucial role in how citizens interact with the state. Interventions can strengthen those habits, but they can also break them, with lasting effects.

For governments, this means that how an incentive is delivered matters as much as the incentive itself. Reward programs that preserve the act of compliance—like raffling physical goods instead of suspending payments—are less likely to cause unintended harm.

And perhaps the most important takeaway: building compliance habits today can reduce the need for heavy enforcement tomorrow. Break those habits, and you may find it hard to make them back.

Authors

Thad Dunning is Robson Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. Felipe Monestier is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Universidad de la República, and Rafael Piñeiro is Professor of Social Sciences at the Universidad Católica del Uruguay. Fernando Rosenblatt is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester, and Guadalupe Tuñón is Assistant Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University.