Supreme Court and Policy Change

While moneyed interests had always approached the Supreme Court for help advancing their goals, the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education opened the door for rights-based groups to use the court system for their fights. Many of these groups seek to upend the legal status quo in pursuit of greater protection of their rights under the law. This litigation is challenging, however, because altering the legal status quo is often viewed as going against the political majority, which the justices are hesitant to do. Unlike their elected counterparts, the justices rely on goodwill and support from the public for their decisions to ensure that they are implemented and enforced, and going against popular sentiment generally means that the “reservoir of goodwill” takes a hit. As a result, many of these groups try to make these difficult decisions easier by garnering public support. One way of doing this is by utilizing counter-stereotypical litigants in very public cases.

What are Counter-Stereotypical Litigants?

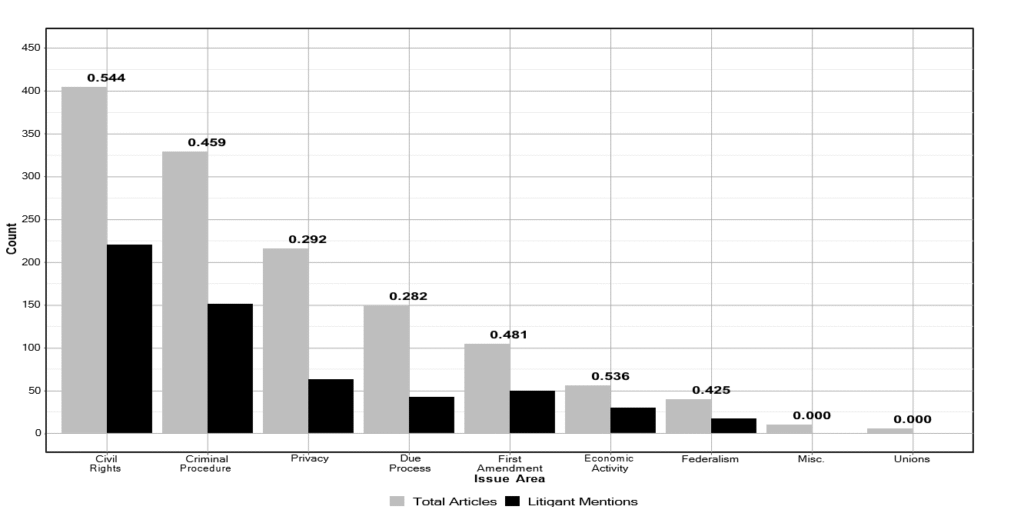

Counter-stereotypical litigants are individuals bringing lawsuits whose identity characteristics appear at odds with the benefit being sought by the case. Because Americans use social group identities to understand Supreme Court decisions and their implications, they often look for cues about how to react, including from the litigants who bring the case. Understanding this, attorneys will sometimes look for litigants whose identities can help them expand the public’s understanding of who benefits from the legal status quo. Given that, in many rights-based cases, the identity of the litigant gets mentioned, as noted in Figure 1, such a strategy might be useful, especially in cases involving civil rights, criminal procedure, and the First Amendment.

Figure 1: Mentions of a litigant in 1,315 newspaper articles covering 112 salient Supreme Court cases heard between the 1998 and 2014 terms, broken down by issue area. Grey indicates the total number of newspaper articles in that issue area across the period, while black shows the number of those articles that mention the litigant. Numbers denote the proportion of articles that mention the litigant.

For an example of this, consider Edward Blum, a well-funded activist who spent decades trying to dismantle affirmative action via the court system. Blum purposefully sought out White women and Asian Americans to bring lawsuits against their respective educational institutions, and he made a point of advertising his litigants’ identities. Why? Because the public believes those groups benefit from affirmative action, and countering that belief could bring more people toward questioning affirmative action’s benefits. That is, the litigants’ identities would alter the narrative about who benefits from affirmative action, which would shift popular sentiments about affirmative action, and ultimately make it easier for the justices to side with Blum’s argument.

Does Utilizing a Counter-Stereotypical Litigant Work?

We seek to understand if seeing a counter-stereotypical litigant increases popular support for a decision seeking to overturn the legal status quo in favor of individual rights. So, for an issue like affirmative action, the public expects that a White person would be the one challenging affirmative action, and the counter-stereotypical litigants would be non-White. We hope that non-White individuals would respond most positively to these litigants because they are the ones who stand to have their perspectives altered by these litigants’ appearances. White individuals generally benefit from the elimination of affirmative action and, therefore, should be supportive regardless of the litigant’s identity.

Black and White Litigants

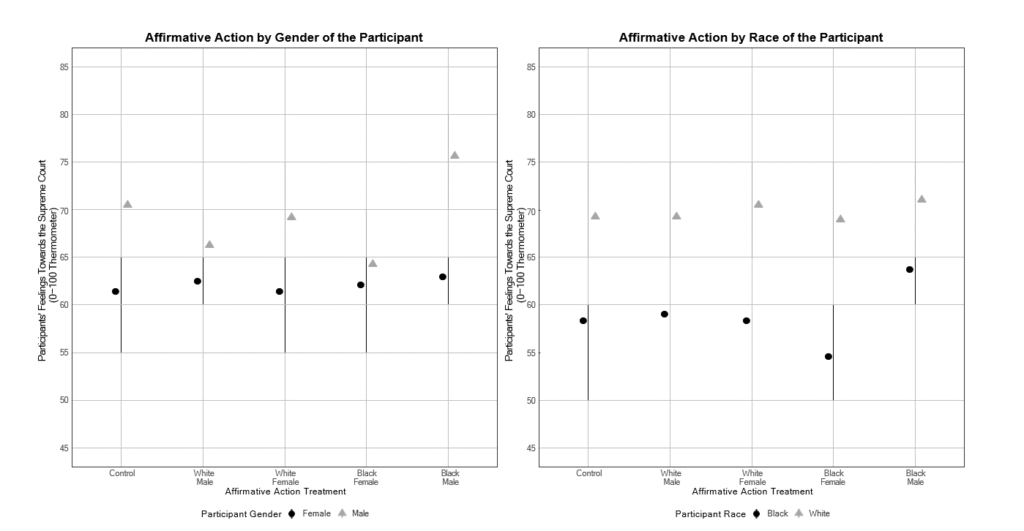

Figure 2: Predicted support for the Supreme Court after reading about a decision overturning affirmative action, broken down by treatment group, based on participant gender (left) and race (right). Vertical bars show 84% confidence intervals to show the probability of confidence intervals overlapping at a 0.05 significance level.

Using a survey experiment, we detailed a case where the Supreme Court overturned a university’s affirmative action program. Then we asked participants about their support for the Supreme Court in light of the decision. In the control group, we did not mention the litigant’s gender or race, but in the other treatments, we varied the litigant’s gender (male/female) and race (White/Black).

As shown on the left side of Figure 2, men consistently support the Supreme Court more strongly, whereas women remain unmoved by the litigant’s case. On the right side of the figure, we see that, like men, White individuals are always more supportive of dismantling affirmative action. We also see that both White and Black respondents are more supportive of the Supreme Court’s decision when a Black man is the counter-stereotypical litigant bringing the lawsuit. These findings suggest counter-stereotypical litigants can increase support for the Supreme Court in light of a decision overturning affirmative action.

Asian American and White Litigants

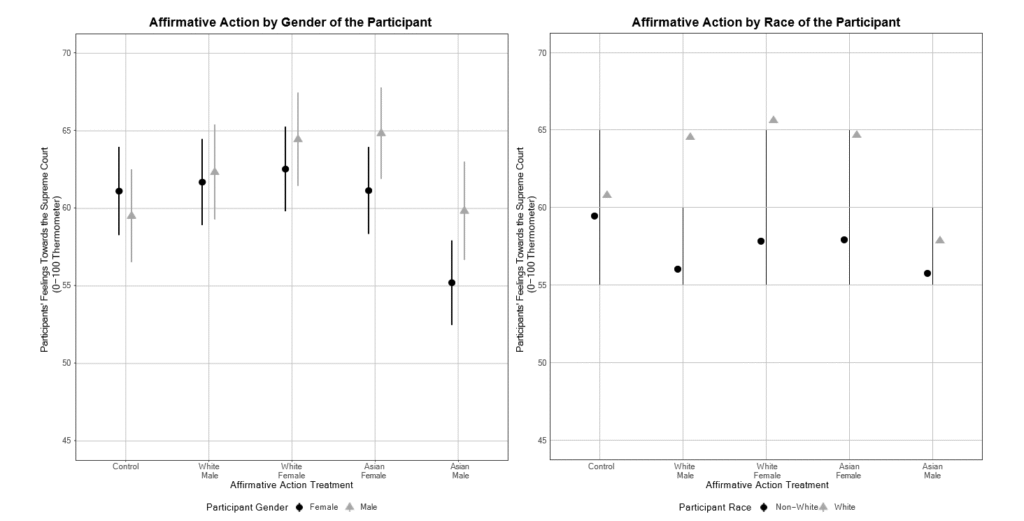

Given the headlines about the Students for Fair Admissions cases against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, we ran the same survey experiment with hypothetical Asian American and White litigants. Per the experimental results presented on the left side of Figure 3, we find no significant differences between men and women. Still, we do find that support significantly decreases among both groups when an Asian American male brings the lawsuit. This could be since Asian American men were the face of the lawsuits, as mentioned earlier. Or, it may be attributed to the fact that it is difficult for participants to believe that Asian Americans, as the “model minority,” need affirmative action, and they thus feel resentful toward the litigant. The right side of the figure reveals that White respondents are overall more supportive of the Court’s decision when other White individuals or Asian women bring the lawsuit. Non-white respondents are once again less supportive, but more willing to lend support when women are the litigants.

Figure 3: Predicted support for the Supreme Court after reading about a decision overturning affirmative action, broken down by treatment group, based on participant gender (left) and race (right). Vertical bars show 84% confidence intervals to show the probability of confidence intervals overlapping at a 0.05 significance level.

Conclusion

Cause lawyers continue to seek ideal litigants to advance the rights of their members. Their goal is to expand support for rights-affirming decisions by convincing people predisposed to dislike a decision that they might benefit from it, which they do by utilizing counter-stereotypical litigants. We find this costly enterprise can work, as is the case when a Black man challenges affirmative action. But we also find that it can backfire, which happens when an Asian American man brings the same lawsuit. These results suggest that attorneys and advocates need to approach counter-stereotypical litigants with caution and truly think through perceptions and stereotypes before they deploy such litigants.

Jamil S. Scott is an Assistant Professor of Government at Georgetown University. Her research examines how race and gender shape the political behavior of political elites and the mass public in the United States. She has been published in the Journal of Politics, Politics, Groups, and Identities, Political Behavior, and the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, among others.

Elizabeth A. Lane is an Assistant Professor at North Carolina State University. Her research interests center on the U.S. judiciary, with a particular emphasis on the U.S. Supreme Court. She has been published in the Journal of Politics, American Journal of Political Science, the British Journal of Political Science, and the Journal of Law and Courts, among others.

Jessica A. Schoenherr is an Assistant Professor at the University of Georgia. Her research interests lie in American political institutions and the U.S. federal court system, with a particular focus on the Supreme Court. She has been published in the Journal of Politics, American Journal of Political Science, Political Research Quarterly, and the Journal of Law and Courts, among others.