Does gender neutrality lead to gender equality?

Does changing legal terms such as “reasonable man” to gender-neutral words such as “reasonable person” impact how women’s cases are decided? In a new article, I find that in criminal appeals, gender-neutral language helps men more than women, while gender stereotypes are more likely to assist women in winning their appeals.

In several supreme courts globally, men and women win criminal appeals at about the same rate (roughly 30 percent). Yet, the basis of the appeal matters a great deal. Men win their cases more often than women when the appeal is based on gender neutral legal due process provisions. For example, the South African criminal code has gender-neutral language when it notes “a person who fails to comply,” Canada’s criminal code is gender-neutral in that “no person shall be convicted of an offence.” However, women win appeals more often than men do when gender stereotypes are introduced in the case. For example, in a drug case, a female defendant may be perceived as co-opted to help their male accomplice, thus increasing her chances of success in court.

The findings suggest that gender neutral language does not lead to equal results, which hinge instead on gendered stereotypes about blameworthiness and crime.

Does gender neutral language help men or women more?

Legal scholars have long assumed that gender neutral language promotes equality. In the twentieth century, legal reforms led to constitutional and statutory changes in language. Rather than references to “man,” “men,” and the use of masculine pronouns, constitutions and statutes were updated to be gender inclusive, referencing “persons,” “the individual,” and “he or she.” These changes communicate to defendants that judges will view their cases equally, regardless of gender. However, are their outcomes the same?

Some legal scholars championed a gender-neutral approach to law. Due process and individual rights protections in criminal law, such as protections against self-incrimination or double jeopardy that were first extended to men, were redefined to be gender-neutral. This shift in legal language applied not just in the U.S. but also in other courts that follow an English tradition. However, not all legal scholars expected gender neutrality to lead to equal results. Others argued that changing definitions in law, seemingly objective, would still lead to unequal outcomes.

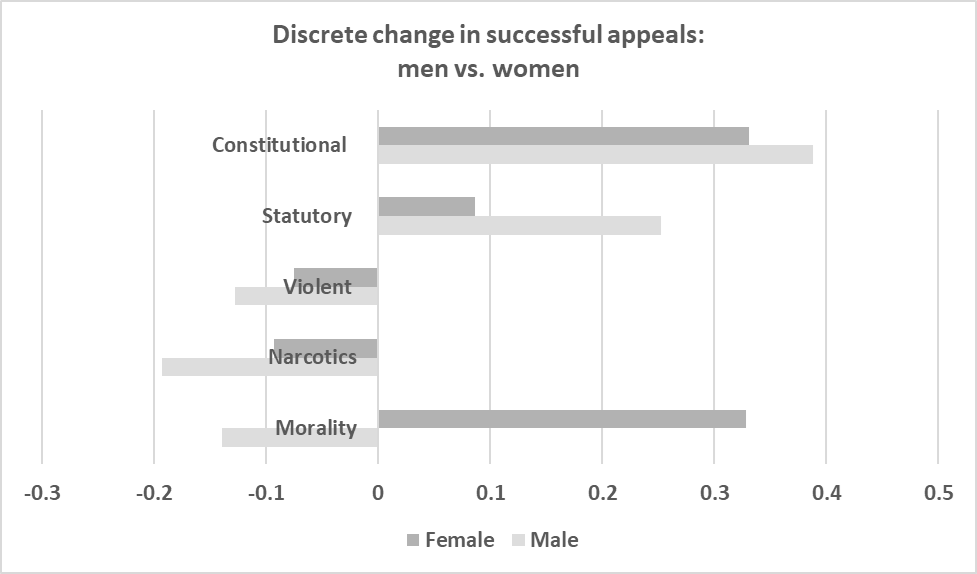

My study evaluates these assumptions in six countries with an English common law heritage – Australia, Canada, India, the Philippines, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. The findings show, as expected, that due process protections help both men and women win their cases more often. However, this success is more pronounced for men, and it is especially pronounced when gender neutral language appears in statutes. Gender neutrality in constitutional texts aids both men and women in winning their appeals at roughly equal rates. However, gender neutrality in statutory texts helps men more than women.

How do gender stereotypes affect men’s and women’s appeals?

If gender neutral legal texts help men more than women win their appeals, then what accounts for roughly equal success rates overall? Some scholars argue that gender stereotypes lead to disparities because women may be viewed as less blameworthy for their crimes. For instance, the stereotype that women are less aggressive than men might lead judges to be less punitive in a violent crime case. Or in a case dealing with narcotics, it might be perceived that women are less culpable because their male accomplice was the instigator. Criminal justice studies show differences in arrests, charges, and sentences, and scholars often attribute more lenient treatment of women as defendants to stereotypes where judges look to protect women from the harshness of the system. And in crimes that historically punished individuals for sexual behavior or other “moral harms,” stereotypes might cause men to be more often viewed as deviants and, thus, punished more harshly.

Using the same data to evaluate this theory, I find that gender stereotypes have a greater impact on women’s successful appeals. While both men and women are less likely to win their appeals if the crime is violent or drug-related, a marked difference occurs in cases that are often characterized as “moral” crimes. Women are more likely to win their appeals in these cases (at about the same rate as if their appeal raised a constitutional protection). In contrast, men are much less likely to be successful. Men are less likely to win their appeals in these cases than they are if their case were related to a crime of violence, such as murder or aggravated assault.

The graph shows the discrete change for men and women when the case involves one of the indicated variables versus when it does not. Negative values show the defendant is less likely to win the appeal, while positive values indicate an increased likelihood of winning.

Were reforms effective?

Gender neutrality in law has lessened disparities to an extent, especially in constitutional texts, but men still win their appeals more often when cases raise a statutory issue. At the same time, stereotypes persist in areas of law where it appears judges are less punitive towards women (and more punitive towards men) in certain categories of crime.

Disparities in law still exist, but with relatively even success rates in appealing their cases, these differences are buried beneath gender neutral legal texts and stereotypes in judging. These differences were previously undetected in studies comparing men’s and women’s cases.

Authors

Susan W. Johnson

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/732948