Voters in democracies regularly have the chance to hold political parties accountable for their behavior in office. That includes taking stock of public policies that benefit some people at the expense of others. Public policies routinely create winners and losers. Targeted government programs, subsidies, tax breaks, or direct transfers benefit certain segments of the electorate more than others.

These policies create politics. Their beneficiaries may reward the politicians who created favorable policies at the ballot box. By contrast, the net payers of redistributive reforms may mobilize against the authors of such policies.

Our research, which centers on a transformational episode of land reallocation in late 20th century Portugal, shows that this is only a partial picture. A more complete understanding of the political consequences of redistributive public policy––including when redistribution can backfire politically on its designers––requires considering how a broader range of voters are impacted and influenced.

Expanding the Audience Beyond Winners and Losers

Major social policies affect more than payers and direct beneficiaries. There are eligible nonbeneficiaries who are legally eligible for a given redistributive program but do not become actual beneficiaries––often because there is greater demand for scarce public resources than governments can satisfy. These individuals may initially support a party promising redistribution and then spurn that party in favor of more radical alternatives once they’ve been left behind.

There are also ineligible nonbeneficiaries who neither directly benefit from government redistribution nor pay for it. The group of ineligible nonbeneficiaries can be large, in some cases outnumbering beneficiaries and payers and making them especially relevant to election outcomes. And given that they are not directly involved or implicated in policy, their views on it are also particularly subject to influence and messaging as a redistributive program is conceived, rolled out, and potentially reversed over successive administrations. The ineligible may initially be worried that they will be subject to taxation or expropriation before reform is implemented, moderate once they realize they are unaffected, and polarize in later periods conditional on their exposure to counter-narratives about the reform.

In Portugal’s land reform, land was expropriated from large landowners (payers) and redistributed to some landless peasants (beneficiaries) but not others (eligible nonbeneficiaries). Small- and medium-sized landowners who fell below a landholding ceiling were ineligible from getting benefits and from being expropriated. Identifying where all these groups were located and how exposed they were to the dynamics of reform reveals a new picture of its political consequences––and one that has implications for redistributive programs elsewhere.

Land Reform and Rollback in Portugal

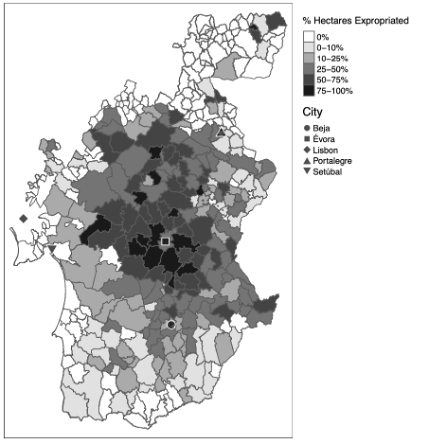

We collected a wide range of historical, quantitative data on Portugal’s land reform in the mid- to late-1970s and paired it with data on political behavior in order to study the varied political consequences of a major program of redistribution. Before land reform, southern Portugal was largely rural and dominated by large estates worked seasonally by landless peasants. The Carnation Revolution of April 25, 1974 upended that arrangement as a group of generals and soldiers under the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) toppled the fascist government in a coup.

Portugal cycled through six provisional governments over the subsequent two years as part of its rocky transition to democracy. The most consequential for the countryside was one led by General Vasco Gonçalves, beginning in March 1975. Gonçalves adopted a radical political agenda aligned closely with the Portuguese Communist Party. His government expropriated around 1 million hectares of land in the south and redistributed it to agricultural cooperatives.

By September 1975, a faction of the MFA aligned with the Socialist Party took control of the government, stalled further redistribution, and oversaw the first legislative elections, which handed power over to the Socialists and its coalition partners. In 1977, the Socialists allowed expropriated landowners to reclaim some of their lands and cut funding to cooperatives. The land reform was further rolled back, sometimes violently, after the Social Democrats came to power in 1979. By 1985, 70% of land had been returned.

Political Reactions to the Reform

To assess the reform’s political consequences, we examine changes in legislative vote share garnered by the major political parties and groupings—the Communists, Socialists, Social Democrats, and radical left—over the course of the land reform and its rollback. We estimate the effect of being exposed to land reform by comparing voting patterns in parishes that received an additional “bump” in land expropriation to similar places that did not.

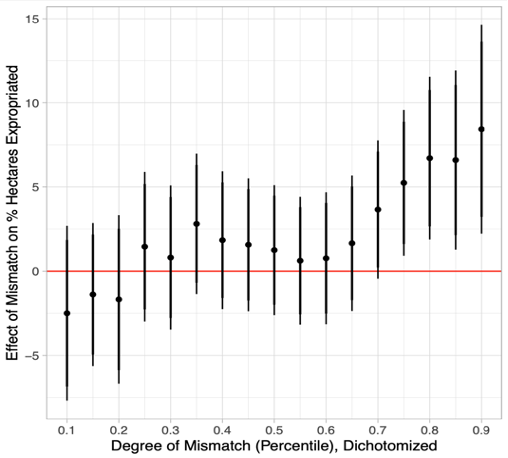

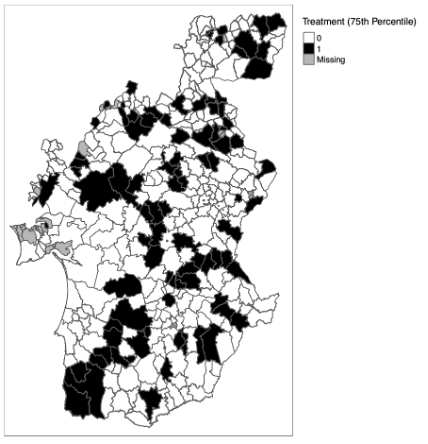

Key to this approach is the fact that the land reform law scored rural properties using a point system, and properties exceeding 50,000 points—estimated based on soil quality and the types of crops cultivated—were subject to expropriation. However, data available to agronomists fifty years ago were poor and impartial relative to modern estimates of land quality based on satellite imagery. By comparing the point system used in 1975 against a modern-day equivalent and identifying differences that are likely the result of poor contemporaneous information, we find that parishes where the point system exceeded comparable estimates of soil quality saw unexpectedly more land expropriated. That enables us to compare parishes that got “extra” land reform (treatment) to those that did not (control)––and to do so among parishes with high overall exposure to land reform and among those with low exposure (see figure/maps).

We assessed the effect of extra land reform on changes to political support between pre-reform elections in 1975 to after reform implementation and rollback (1976-1987). Parishes with low overall land reform intensity that received an extra bump in land reform experienced a shift away from the Communists and towards the radical left, which promised to push reform further. By contrast, Communist support held in high reform intensity parishes with extra land reform where beneficiaries dominated. The Right lost about half of its support in these parishes, likely driven by ineligible individuals who were relieved that they did not get swept up into the reform and moderated.

We also estimate shifts in political support after the controversial and polarizing land reform rollback. Payers, beneficiaries, and eligible nonbeneficiaries retained their loyalties; political changes were driven by appeals to ineligible beneficiaries by the right and left. The Center therefore lost support to both sides amid polarization.

The Unintended Politics of Policy

Public policy has political consequences not only among direct winners and losers, but also among those who ought to be beneficiaries but are excluded, and groups not directly impacted by policy reform but that are still subject to political narratives surrounding it. Recognizing that helps to account for unanticipated and unintended policy consequences––including political backfire for policy reformers themselves. An understanding of those dynamics can help with designing successful and durable policy reforms that level the playing field within society.

Authors

Michael Albertus and Noah Schouela