Political inequality does not stop at the doorstep of political office. Women who overcome the political glass ceiling and win elections, often against the odds, continue to face discrimination and attempts at erasing or diminishing their influence over decision-making once they are in office.

Two main mechanisms can explain why elected women continue to face such hurdles after election. On one hand, the persistence of these inequalities may partly stem from the relative absence of experience or networks among the first generations of elected women. On the other, discrimination from traditional (male) elites is however also likely to drive these processes: women who manage to win elections in patriarchal contexts may for instance face political exclusion or bias from higher-level authorities and bureaucrats, or from other members of the institutions whose ranks they have joined. This may be because these predominantly male actors continue to harbor biased beliefs about women or because they altogether disapprove of the idea of women entering the political realm. Such discrimination is consequential: women may be excluded from strategic meetings; their input may be disregarded or ignored; and they may be interrupted if and when they find avenues to influence political deliberations.

Quotas and their limits

When such political inequality exists, gender quotas in politics – however ambitious they may be on paper – may not suffice to enable women politicians to have an equal say in policy outcomes.

In an article recently published paper in the Journal of Politics (“Who Actually Governs? Gender Inequality and Political Representation in Rural India”), we provide the first objective evidence that the extensive electoral quotas which have enabled women to head a high proportion of villages across rural India since the mid-1990s do not close the gap in political influence between men and women. In 1992, the 73rd and 74th Indian Constitutional Amendments devolved considerable power to the local level and mandated that village councils “reserve” seats for women and members of lower castes. However, public perceptions and anecdotal accounts suggest that quota-elected women politicians act as “proxies” for other political interests once in office. Our work is the first to document the scale of this phenomenon, popularly known as rule by the “sarpanch pati:” the quota-elected head’s husband. As the democracy with the largest set of quotas for traditionally excluded groups, India presents an important test of whether political institutions can alter longstanding patterns of political exclusion.

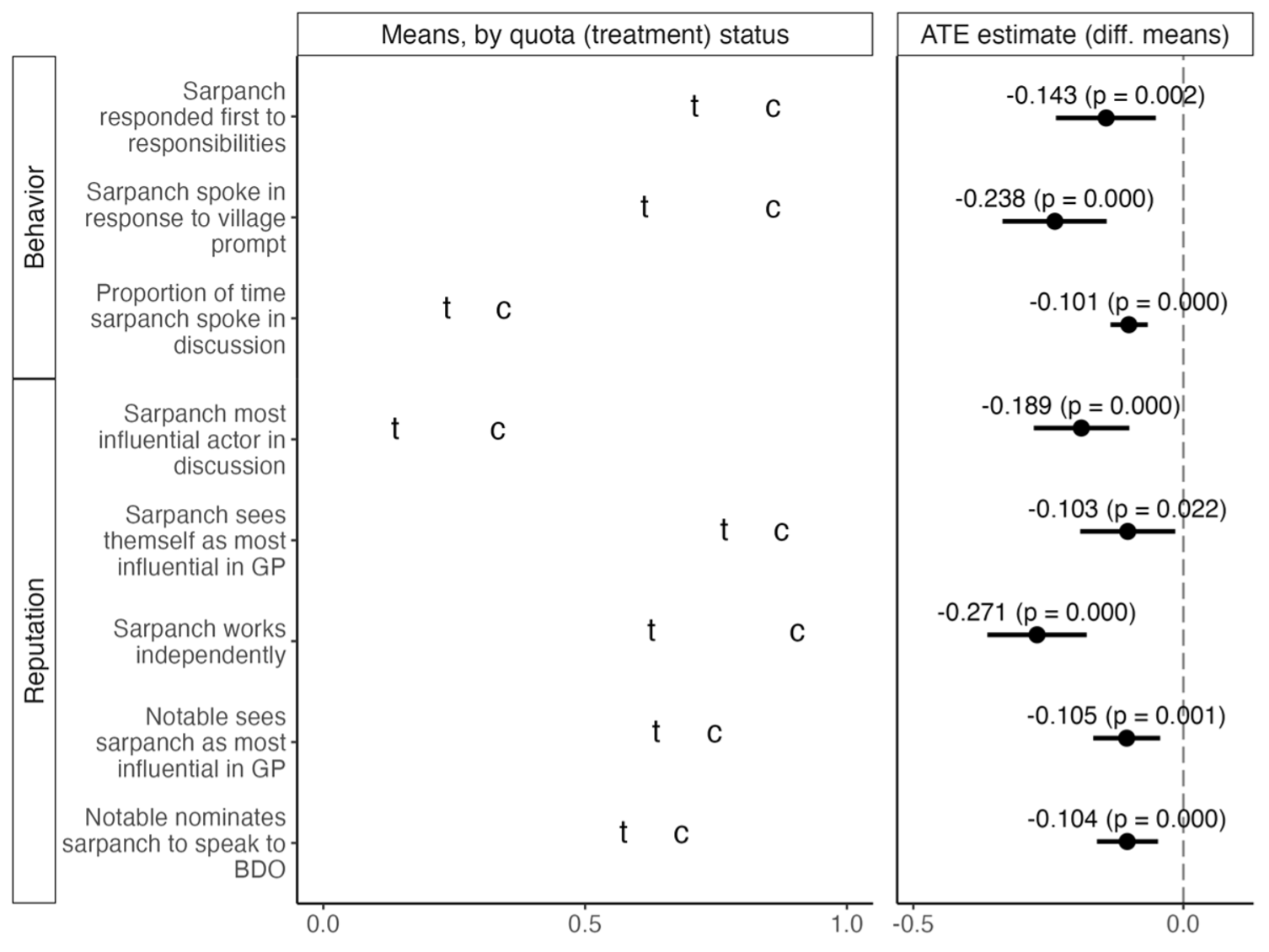

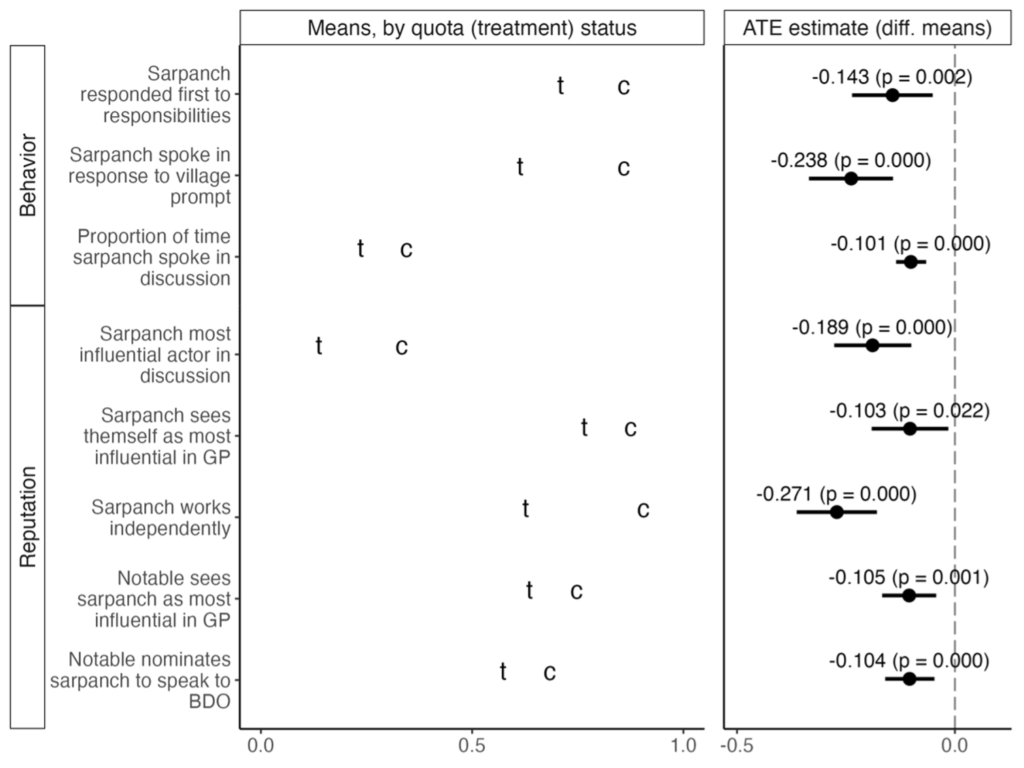

Drawing on original micro-level data from 320 Indian villages, we map the extent to which women with varied levels of skills and privilege influence politics once elected via quotas. We document variation in the centrality of elected officials, focusing on their voice and role in decision-making processes. That is, we study the extent to which men and women officials exercise voice and influence in political deliberation, are seen as occupying a central role in decision-making, and are perceived as central in governance more broadly.

Measuring Political Inequality in Office

Measuring the extent to which officials “actually” govern in institutions of collective decision-making bodies is challenging. To overcome this, we leverage behavioral and reputational measures to shine light on this underappreciated political inequality among already-elected officials. As shown in the attached illustration, across eight measures of voice and reputation in decision-making, women elected via quotas (t in the graph) face disproportionate barriers to decision-making after they reach office. Women elected to head councils tend to let other members of the village council speak first (first two items), they say less overall (3rd item), and they are less likely to be seen as less influential actors by villagers and by the officials with whom they share responsibilities compared to (mainly men) heads elected outside quotas.

Our analyses suggest that this form of gendered political inequality owes to interference and discrimination by others, alongside underlying structural inequalities that constrain the influence of quota-elected women officials. Quota-elected women are different from the predominantly male officials elected outside quotas. They are younger, less experienced, less educated, and less connected. At the same time, however, much suggestive evidence we present confirms that discrimination by male village council members and village bureaucrats drives these effects. Our systematic interviews of the main actors in villages show that biased opinions about the ability of all women – quota-elected or not – to serve as political leaders are rampant. We also show these local elites tolerate interference in elected women’s work. We provide detailed qualitative evidence that further substantiates the important role of male elite interference in upholding a system of “proxyism” that constrains quota-elected women leaders. In sum, gendered bias and interference are widely tolerated, and hence likely frequent obstacles to elected women’s influence over decision-making in governance.

Beyond Proxy Politics: The Road Ahead

Gendered political exclusion post-election undermines the potential link between descriptive and substantive representation. Without voice and centrality in the decision-making that is the core work of elected leaders, we cannot expect politicians from historically marginalized groups to advance policies that benefit their groups or the collective community. This may also have a chilling effect on broader political engagement by members of disadvantaged groups, reinforcing potential fears about their political inefficacy. For this reason, social scientists and policymakers should acknowledge this underappreciated form of political inequality –centrality in decision-making– to comprehensively understand the impact of descriptive representation. This article documents that quota-elected women’s limited political agency once in office does not owe exclusively to household-based interference, contrary to popular consensus in India. To move beyond “proxyism,” it is necessary to understand how the male-dominated elite ecosystem of political actors interferes in women’s role as political leaders and effectively silences them once in office. Beyond quotas, complementary interventions enabling women to overcome political experience and network disadvantages are likely necessary. So too are sanctions against elites who appropriate or minimize women representatives’ roles. These additional steps are likely important complements to ensure that gender quotas generate substantive change in citizen representation and governance.

Authors

Alyssa Heinze, Rachel Brulé and Simon Chauchard