“Cancel culture” is misunderstood

Political commentators worry that Americans have become too quick to socially or economically sanction those who make offensive statements — what’s often called “canceling.” The recent attacks on Tesla products because of Elon Musk’s actions as the head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are the latest example of this behavior. But how often do ordinary Americans sanction others for offensive speech? And what motivates people to engage in canceling behavior? We explore these questions in a newly published article based on an original survey and conjoint experiment from 2021.

How commonly do Americans cancel?

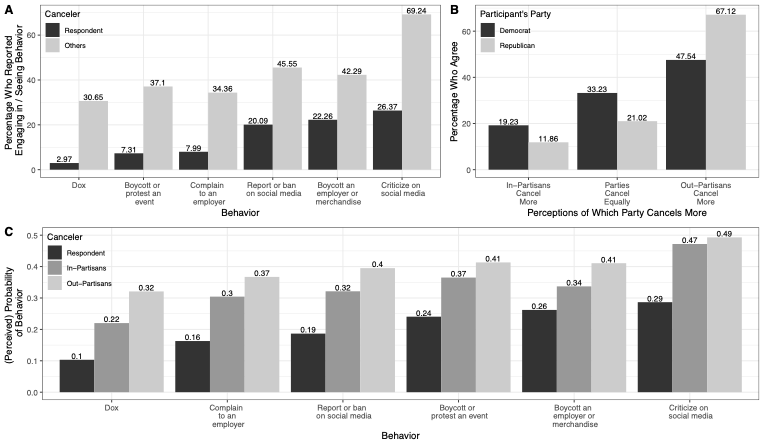

A striking finding from our study is that Americans vastly overestimate how often canceling occurs. Only a minority of respondents reported engaging in any of the six sanctioning behaviors that we consider: doxing, boycotting or protesting an event, complaining to a speaker’s employer, reporting a speaker on social media, boycotting a company or product, or criticizing a speaker on social media. However, they perceived others, especially other political party members, to engage in every canceling behavior at much higher rates. This gap between perception and reality suggests that media coverage and partisan rhetoric fuel exaggerated fears about cancel culture.

Figure 1: Americans Overestimate How Much Others, Especially Out-Partisans, Engage in Canceling

Note: Panel A shows how often respondents saw others engage in each canceling behavior in the “real world,” relative to how much they engaged in those behaviors. Panel B shows how often respondents thought real-world canceling behavior came from the out-party versus the respondent’s in-party. Panel C shows how likely, in our conjoint experiment, respondents felt they, in-partisans, and out-partisans would engage in each canceling behavior.

Why do Americans cancel?

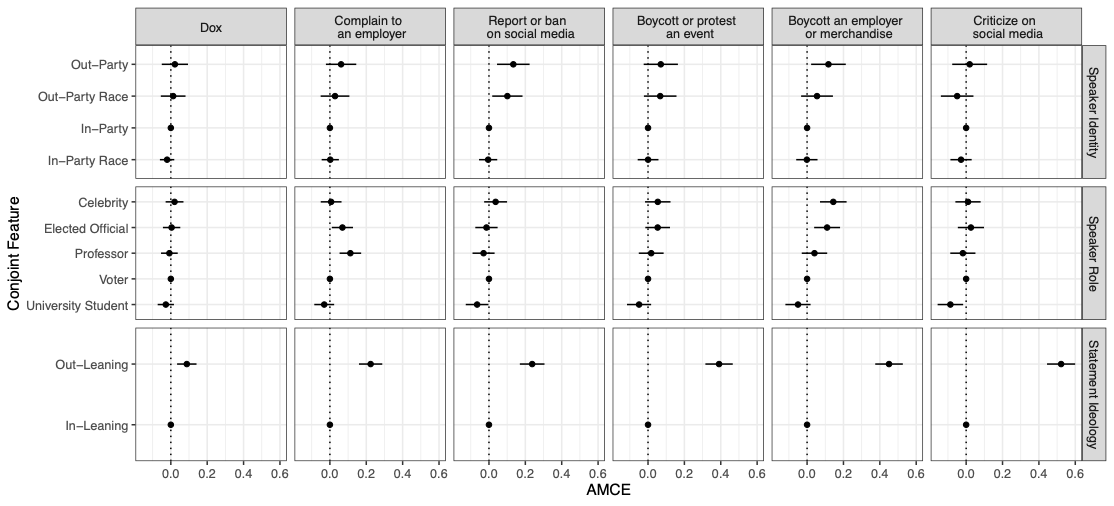

Our study also challenges a common assumption about what motivates canceling behavior. Some have claimed that canceling behavior is primarily driven by personal dislike of individuals—particularly members of the other party—rather than principled disagreement with a speaker’s statements. In other words, instances of canceling amount to little more than disingenuous partisan attacks. However, Americans tend to sanction statements that offend their ideology, regardless of who says them. For instance, Democrats were more likely to oppose statements that they saw as racist, while Republicans were more likely to reject statements they perceived as unpatriotic. This was true even when the statements were made by a speaker from the same party as the audience member.

Figure 2: Americans Cancel Disagreeable Statements, Not Disliked Speakers

Note: This figure shows which factors drove respondents to engage in each canceling behavior in our conjoint experiment. Points and bars represent AMCEs and 95 percent confidence intervals.

Do Democrats cancel more than Republicans?

Finally, a key debate in cancel culture discourse is whether one political side is more guilty of canceling than the other. While media narratives often frame cancel culture as a left-wing phenomenon, our study found that Democrats and Republicans engage in canceling at similar rates when presented with comparable scenarios. However, Democrats were more likely to report having canceled in the real world when we collected our data. This difference may be because, at the time of our study, Democrats may have been exposed to more “cancelable” statements.

Conclusion

In sum, the findings of our study challenge many of the prevailing narratives about how Americans respond to offensive speech. While canceling does occur, it is far less prevalent than people assume. Canceling is primarily driven by genuine disagreement rather than partisan bias. Finally, canceling is a bipartisan phenomenon. We think these findings are important: When people believe that canceling is rampant—or that they may be canceled simply because of who they are—they may self-censor even when their statements are unlikely to trigger backlash. Moreover, the widespread misperception that those from the other party cancel frequently could exacerbate partisan animus and limit contact between disagreeing citizens.

Author

Nicholas C. Dias, James N. Druckman, and Matthew S. Levendusky