Author: C. Funk | Rats Project Lab at UB | July 9, 2015

Thanks to the efforts of twenty or more undergraduate students, graduate students, and researchers at UB and Hamline University our ¼ inch screen bulk samples from the KIS-050 village midden are sorted to component parts. Samples of identified fish, bird, and mammal elements are in the isotope lab at UAF. Mammal bone elements are being identified by the Hamline team, birds by the UB team. Stone tools go to Hamline, bone tools stay here at UB.

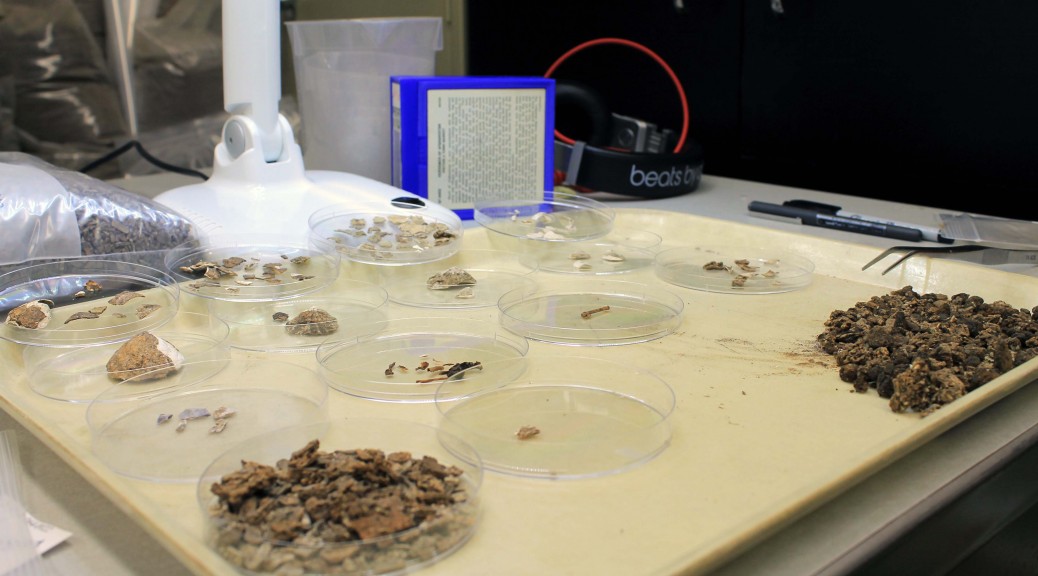

This month the invertebrates from the bulk samples will receive our focused attention. Josh Howard, a graduate student working in the Rats Lab at UB this summer and I are sorting, counting, weighing, and starting to identify the invertebrate assemblage from the ¼ inch bulk sample fraction. We measure whole lantern pyramids (mouth parts) from Strongylocentrous spp. (sea urchins) to track their size over time. Smaller urchins may indicate periods of heavy harvesting and signal community shifts in the local intertidal zone. Limpet size shifts may similarly signal ecological changes, but most of the limpets are fractured and impossible to measure – their little hat tops, the apex portions, are separated from their wide brims.

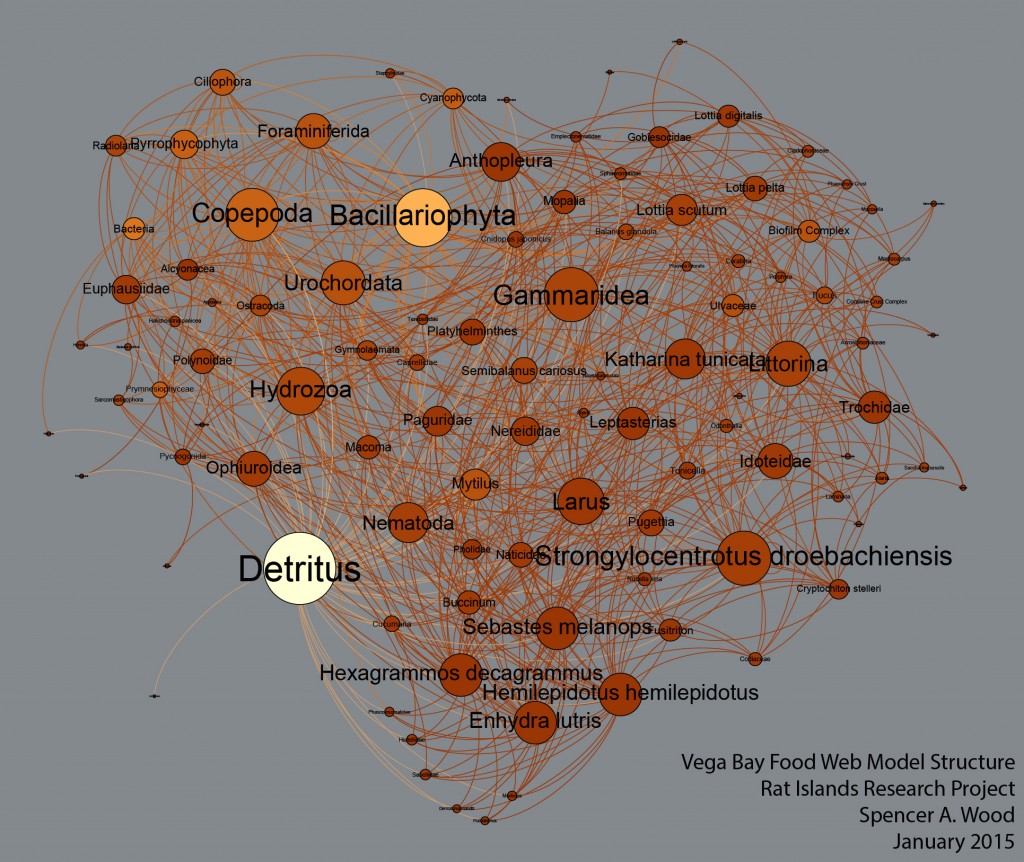

Periwinkles and other gastropods, mussels, and chitons live in the modern rocky intertidal zone near the archaeological site, but they are poorly represented in the archaeological assemblages. We count the hinge fragments of mussels and the whorls of gastropods to learn how many are present in a sample. The numbers are variable, but low for each bulk sample – less even than one serving of bouillabaisse or Portuguese caldeirada de peixe might have in it. We’d be happy to count chiton plates, if only they were present in the prehistoric occupation debris of KIS-050. We thought they should be present, since our team ecologist saw so many in the modern intertidal zone.

Archaeologists in the Aleutian Islands tend to think of prehistoric sites and reefs as paired – reefs can be rich resource areas. But as our work continues to demonstrate, prehistoric Aleut use of these resources was complex. The details of which invertebrates were harvested, where they were eaten, and how people disposed of them remain obscure to us. Measuring invertebrate abundance, size, and community parameters will tell us more about the circumstances of Aleut choice – what species were even available to eat in the dynamic intertidal environment?