Author: C. Funk | University at Buffalo | October 9, 2014

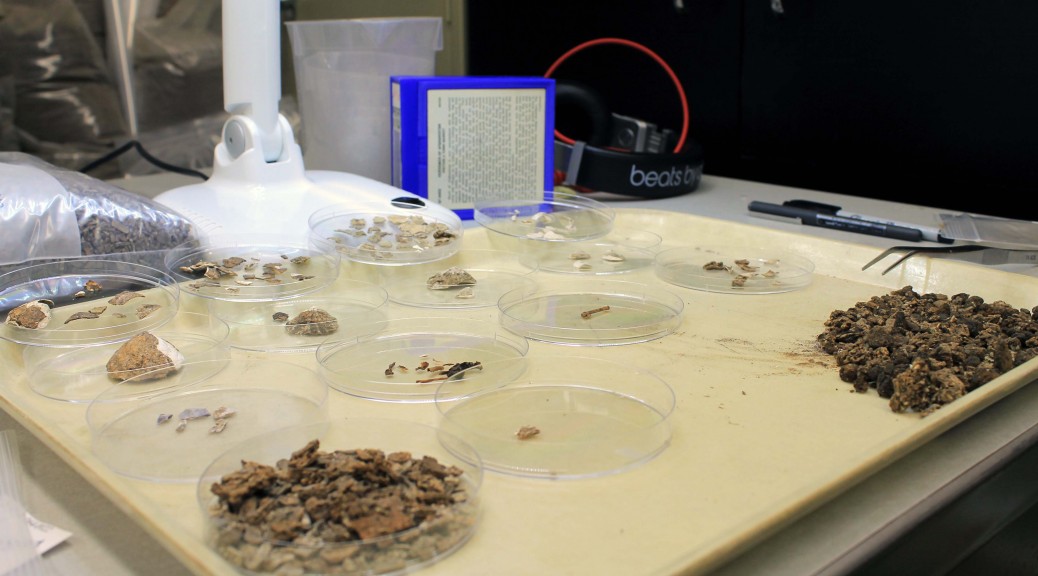

We’re working here in the Rat Islands research lab at University at Buffalo. It’s a Thursday afternoon – outside it’s windy and sunny, a perfect fall day. In here the lights are shining brightly on Ariel, Bobbi, and me. Bobbi is cataloging bone tools and I’ll talk to her about that a bit next week.

Today I’m interested in what Ariel is doing.

Today I’m interested in what Ariel is doing.

Ariel is a second year graduate student here in the department. She is planning to specialize in monumentality and colonialism in Europe for her dissertation research. She happens to have a skill set in bird osteology and that’s why she’s here with us.

“What are you doing over there?” I ask her. She rolls her eyes at me a little bit because I can clearly see what she is doing, “sorting a sample bag of bird bones into elements,” she says. After a moment she says, “I think this is just one bird, part of the thoracic area and the wings. The vertebrae are articulating and the tarsometatarsi are paired.” We do a quick check in the bird book and it seems to be a small cormorant. Our comparative osteological collection will arrive from the Burke Museum in Seattle next week. We’ll identify the bird then.

Bobbi and Ariel and I are talking about excavation sampling strategies and their impacts on which elements were collected and on the patterns of bone presence we’ll use to talk about Aleut resource exploitation, processing, and discard strategies. Ariel says that she thinks she is seeing more humerii and ulnae in general – those are the bones in the bird wing. But some samples have a higher concentration of leg elements. “Mostly,” Ariel looks up at me from her study of the bones on the table, “mostly we seem to have more wings than butts.” Bobbi looks interested at this. “Maybe they were making a lot of bird butt hats. In the field, Debbie said Aleuts made duck butt hats for babies. They cut the legs off and sewed the thighs so the feathered legs stuck up like feathery little ears.” We talk about wearing bird butt hats for a bit before we settle back into work.

Bobbi and Ariel and I are talking about excavation sampling strategies and their impacts on which elements were collected and on the patterns of bone presence we’ll use to talk about Aleut resource exploitation, processing, and discard strategies. Ariel says that she thinks she is seeing more humerii and ulnae in general – those are the bones in the bird wing. But some samples have a higher concentration of leg elements. “Mostly,” Ariel looks up at me from her study of the bones on the table, “mostly we seem to have more wings than butts.” Bobbi looks interested at this. “Maybe they were making a lot of bird butt hats. In the field, Debbie said Aleuts made duck butt hats for babies. They cut the legs off and sewed the thighs so the feathered legs stuck up like feathery little ears.” We talk about wearing bird butt hats for a bit before we settle back into work.

I ask Ariel if she has worked with birds at other sites. She has. She worked on the Pompeii Archaeological Research Project: Porta Stabia. But she worked with flotation samples there, so the specimens were small and fragmented. She says that the Rats materials are larger, that there are more whole elements, and that the preservation of this collection is excellent.

“Why birds?” I ask Ariel. “Because another researcher asked me what I’d like to look at. I picked birds because I don’t want to do fish and it turns out birds aren’t studied often. People think they are difficult but they are actually easy to identify to family. There’s a lot of room for research.”

I’ve stopped bothering Bobbi and Ariel and they are working away. I can hear the bones shuffling around on the table in front of Ariel, and the keyboard clattering while Bobbi enters artifact catalog data on the lab computer.

I’ve stopped bothering Bobbi and Ariel and they are working away. I can hear the bones shuffling around on the table in front of Ariel, and the keyboard clattering while Bobbi enters artifact catalog data on the lab computer.