Authors: Caroline Funk and Spencer A. Wood | February 20, 2015

Our team marine biologist, Dr. Spencer Wood, is building food webs as part of his research on marine communities. Spencer spent the 2014 field season in the intertidal zones near prehistoric Aleut village sites. His gear and clothes weighed more than he did; most days he went out into the rocky reefs wearing five or six layers of long underwear, fuzzies, and raingear – topped by warm hats and a PFD. He recorded the presence of species and counted them using formal data-collection procedures. Spencer also collected small tissue samples from some of the species, for isotope analysis in Dr. Nicole Misarti’s lab (see our previous post “Intertidal Foodweb Analysis” and the Wig-L-Bug video coming soon).

Back in his office in Seattle, Spencer digitized his field data and combined them with information from an existing database of the known trophic relationships between species – who eats whom in the ocean. By melding observational data from the field with other information on the characteristics of the species that he observed, Spencer is able to create interesting depictions of the ecological communities that show how species are linked together into food webs around ancient village sites.

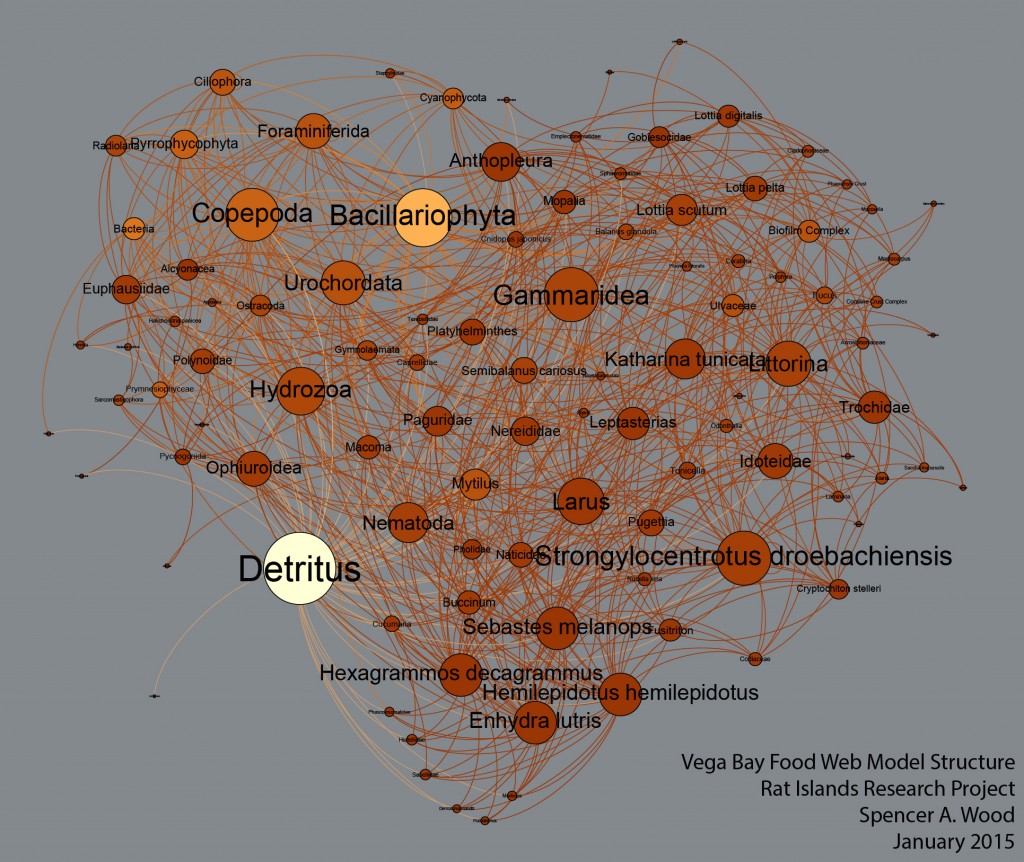

The Vega Bay Food Web Model

The image here is a visual representation of the food web of the modern Vega Bay intertidal zone. It depicts the species (or taxonomic groups) present, their prey and predators, and the number of relationships among them. The image shows a network of predator-prey interactions. The size of the circle, called the node, indicates the number of links that any given taxon has with other taxa. A large diameter node indicates many connections. Lines curving clockwise from one node to another depict a predator eating its prey. Lines that curve counterclockwise indicate prey are being eaten by a predator.

Look at Bacilariophyta (diatoms) and Detritus (material from dead organisms) in the food web. These nodes are large, which means that they are linked to many other taxa. But, the links to them curve counterclockwise, which means that are being consumed by organisms like zooplankton (Copepods), snails (Littorina), and chitons (Mopalia). Gulls (the Larus node just right of center) have links that curve in both directions, showing that gulls are both a predator and a prey, depending on who they encounter.

Today people do not inhabit the region, so they are absent from the modern food web diagram. In the past, however, prehistoric Aleuts ate a wide variety of plants and animals from the intertidal zone and would be represented in a prehistoric food web as a large node with links to many different prey.

What Can We Learn From Food Webs?

Food webs are useful for understanding and predicting how changes will impact ecological systems. Fish and wildlife managers, for example, use them to estimate potential impacts of fishing and hunting and to set quotas. Other scientists use them to predict how changing temperatures will impact ecosystems. Our team is using the new food webs for Vega Bay and other sites in the Rat Islands to understand whether marine communities function differently today than they did thousands of years ago. Our team is also using information from our archaeological studies to construct food web depictions of ancient intertidal communities, from time periods when people lived in the Rat Islands. Including humans in these large, data-rich food web models allows us to better understand people’s relationships with other species in the marine environment. Soon, we’ll begin including other types of interactions into our networks, beyond just links between predators and their prey. We want to know more about the “non-trophic” roles of people, as culturally motivated resource collectors and members of the ecological community, and how they have impacted and been impacted by the dynamic environment over millennia.