Inorganic & Organometallic Synthetic Chemistry

We study the chemistry of first-row transition metal compounds

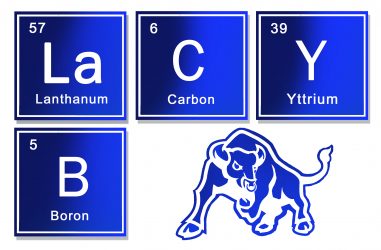

At the University at Buffalo, the Lacy group explores inorganic and organometallic chemistry as a means of building matter with atomic precision. While the construction of everyday objects follows long-understood rules, the assembly of matter at the molecular level—atom by atom—is governed by principles still being uncovered within the chemical sciences. Our group approaches this science using the tools of first-row transition-metal coordination chemistry. By following the logic of synthesis, we identify gaps in chemical knowledge and use experiment to bridge them. Our ongoing story of discovery centers on manganese(III) halide and pseudohalide complexes, a new class of compounds with unique properties. Through persistence and design, we uncovered their remarkable capacity for high-potential redox chemistry, opening new directions in synthesis and deepening our understanding of Mn’s role in life and planetary chemistry.

Our mission is to train undergraduate and graduate students to think independently, question assumptions, and apply these ideals in whatever careers they pursue. By teaching synthesis as both a technical discipline and a way of reasoning, we aim to cultivate scientists who can recognize gaps in understanding and have the creativity and rigor to fill them. This philosophy draws inspiration from *David Deutsch’s vision of knowledge as the ultimate driver of progress—that problems are inevitable, but so are solutions, provided we continue to deepen our understanding. In that spirit of optimism, our work seeks to discover new forms of matter, new reactivity, and new truths about how the material world organizes itself, confident that in doing so, we participate in the endless creation of knowledge that defines science at its best.

Why Mn(III)?

Our focus and expertise on the chemistry of iron, manganese (Mn), and titanium stems from their being the three most abundant transition metals. Iron and Mn are also biologically important and central to life on Earth. Our current main focus is the element Mn, because of two intriguing questions our discoveries may help address. One concerns its role in the evolution of photosynthesis: what is the molecular nature of Mn(II) oxidation that led to the formation of the water-oxidizing cluster in extant photosystem II? The second involves a mysterious role of Mn in the degradation of recalcitrant organic matter: what is the molecular basis of this degradation, and does this process have synthetic utility? A central hypothesis in addressing these questions—where only Mn carries out the relevant chemistry in nature—is that Mn(III)’s high one-electron reduction potential is the key property that has literally shaped the planet’s chemistry. Yet despite this natural importance, chemists have struggled to fully answer these questions. The reason is that replication of this high-potential property of Mn(III) is very difficult to achieve in synthetic molecular species. Without access to the appropriate forms, generations of chemists have relied on only a narrow subset of low-potential manganese compounds.

Our group has begun to change that. By developing stable manganese(III) tri-halide and tri-pseudohalide complexes for the first time, we have uncovered a new class of compounds that capture manganese’s extraordinary natural oxidizing power. This discovery originated from a seed of curiously: if CrCl3 and FeCl3 are stable compounds, where is MnCl3? Pondering such esoteric questions as this is what we do.

Our goals

Our discovery of stable manganese(III) tri-halide and tri-pseudohalide complexes has opened a new frontier in inorganic chemistry. These compounds reveal reactivity that had never been observed for manganese and we are now working to understand how and why these reactions occur. Our mediate goal is defining the mechanisms that govern Mn(III)-mediated bond formation and oxidation, using the full range of tools in modern physical inorganic chemistry. Through synthesis, spectroscopy (UV-vis, EPR, XAS), and emerging techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy, we aim to reveal how complex structure and redox potential govern reactivity. Using this knowledge, we seek to demonstrate how this new chemistry can influence other fields. One central objective is to chart the scope of undirected C–H bond functionalization—a long-standing challenge in organic chemistry. Another goal is to harness the reactivity of transient Mn(IV) intermediates—generated through Mn(III) disproportionation—with relevance to catalysis and formation of the water oxidizing cluster in photosynthesis. We are also applying the insights gained with other transition metals, particularly iron, titanium, and molybdenum, and we are tackling the surprisingly difficult challenge of synthesizing Mn(I) carbonyl compounds under safe, inexpensive conditions. If you’ve read this far, it’s worth pointing out that we also occasionally ponder the meaning of life and the nature of reality, which tends to happen when one spends too much time contemplating the arcane details of transition metal coordination chemistry.

• Unprecedented access to the chemistry of MnCl3

https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c08509

https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c03651

• Demonstration that MnIIIX3 compounds are high-potential compounds

https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c03411

• Phosphine coordinated MnIIIX3 complexes

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c01820

• Ligands tune the reactivity of MnIIIX3 complexes

https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29194670