There has been a decade-long search to understand what has been called “Africa’s growth tragedy,” where standard economic policies have not significantly reduced the wealth gap between Africa and countries from other continents that also emerged as independent post-World War II. The proposed culprit for this persistent gap is the burden of ethnic diversity, especially prominent among African countries. However, why this might be the case has yet to receive a few credible answers.

Measuring Language Policy

Our research, “The Historical Sources of Language Policy,” culminating in our publication in the Journal of Politics, suggests that language policy plays a critical role in shaping socioeconomic outcomes and human capital development across nations. In our initial publication, which relied on language trees developed by linguists, we computed what we call the Average Distance from the Official Language (ADOL), calculated as the linguistic distance between the mother tongue of the ethnic groups and the country’s official language. Each ethnic group would have a score, and its percentage in the population would determine its influence in the overall ranking. ADOL was computed as high if the official language were from a different language family from that of a constituent group in the country (e.g. English is from the Indo-European family vs. Yoruba, which is a member of the Niger-Congo language family); but low if the difference was between members of the same family (e.g. Castilian and Catalan are both Romance languages).

Evidence of Policy Failure

Cross-country correlations revealed that lower ADOL scores are associated with higher cognitive skills, longer life expectancy, and higher GDP per capita. In comparison, higher scores were associated with lower scores on human development indices. This idea was confirmed in experiments in Cameroon and Ethiopia, where ADOL was reduced when indigenous languages were promoted in public education. Primary students who were taught in their mother tongues outperformed matched classes where a European language was retained as the medium of instruction.

Whither Colonial Languages?

Due to the hope of emigration to advanced labor markets, parents throughout Africa support the use of colonial languages in their children’s education. There is, therefore, no significant political movement pressing for indigenous-language education. However, after more than 50 years of using colonial languages as official, as in the medium of instruction in public schools, knowledge of them remains severely limited within society. Indeed, with the colonial medium of instruction, low percentages of primary six graduates can read a sentence in any language. Our data show that the proportion of literate individuals in countries where the indigenous language is the sole official language (73%) is vastly greater than in countries where the colonial language is the sole official language (48%).

One reason why public education in colonial languages fails to achieve functional literacy in Africa is that students rarely converse with speakers who have native fluency. The teacher corps themselves are deficient in English. Truly fluent teachers can get better jobs outside the school system, even through emigration. Our data show that children who converse in standard English outside of school–e.g., with their well-educated parents – compared to students whose parents are equally well-educated but converse at home in an indigenous language, are better able to read a sentence after primary school.

Explaining why Africa is Different from the Tigers in Asia?

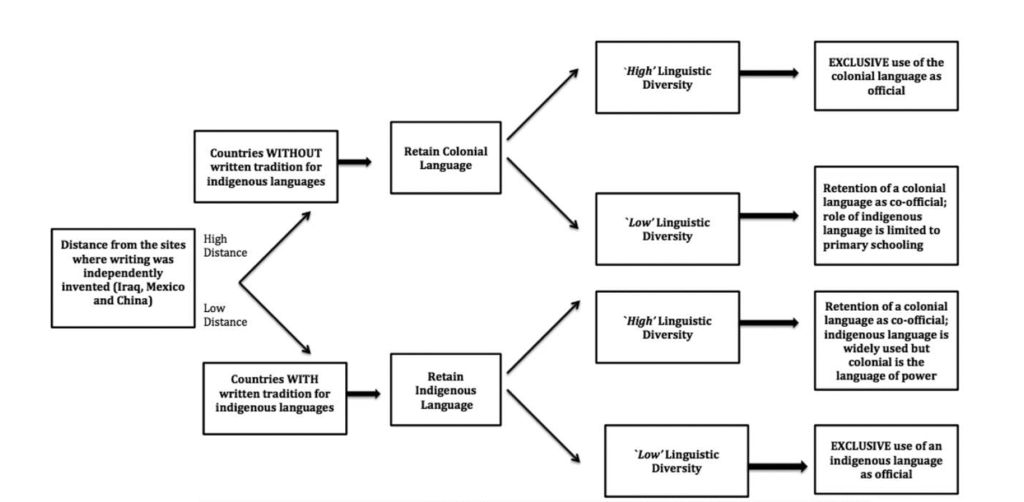

But why ineffective language policies? In our Journal of Politics article, we propose a model that highlights two critical factors influencing language policy: the existence of a pre-colonial written tradition for a major language group and the degree of linguistic fractionalization within the country. A flow diagram below predicts four distinct language policy outcomes based on these constraints: exclusive reliance on the colonial language, exclusive reliance on an indigenous language, and two cases of co-official status, one favoring the colonial language and the other favoring an indigenous language.

Figure 1. The Theoretical Framework

This framework suggests that a country’s written tradition is the first factor that lowers the costs of making an indigenous language official. Countries with well-developed written scripts for their indigenous languages are more likely to preserve an official role for them. Indeed, the data show that all 70 countries that had a written script (mostly Asian) retain the indigenous language to act (at least) as (co-) officials. Conversely, all 53 countries without a written script (mostly African) retain the colonial language to act (at least) as (co-) officials.

But what explains the lack of a written tradition for most African languages? Our data show that the geographic proximity in ancient times from the few places where writing was invented is consequential. Countries proximate to regions where writing was invented were more likely to have adopted a script for their languages. Additionally, geographic zones where grains could be stored – and therefore a need to keep records – were more likely to have developed writing systems. Africa lost out on both these counts.

The second factor, the level of linguistic diversity within a country’s inherited colonial boundaries, then comes into play. Higher linguistic diversity increases the costs of implementing curricula that rely on indigenous languages as the medium of instruction.

For countries with a well-developed writing tradition and high linguistic diversity (e.g., Pakistan, India, Singapore), they often designate their major indigenous language(s) as co-official, while retaining the colonial language. In contrast, countries with a major group that has a written tradition and low linguistic diversity (e.g., Armenia, Cambodia, Libya, Vietnam) rely exclusively on their indigenous languages for administrative and educational purposes.

Meanwhile, in Africa, nearly all countries are highly fragmented, and in none of them is an indigenous language the sole official language. Those with low linguistic diversity, such as Rwanda, Burundi, and Eswatini, are more likely to rely on them as a medium of instruction in early primary years. Still, the colonial language is reserved for all high-status domains. In countries with high fragmentation, colonial languages are more likely to be the sole official language. The combination of a lack of a writing tradition of any major indigenous language and high diversity leads to policies that disfavor the development of human capital.

Policy Implications

Our research suggests two potential routes that enable the full development of human capital to overcome Africa’s growth tragedy. First, institutionalizing in education a language (or languages) that is (are) proximate in structure to the related indigenous languages of the population. Making them official would approximate the policies of the small European states. These states offer high-quality indigenous language instruction through secondary school to their populations, along with intensive instruction in English, making them well prepared for higher education through the English medium. This would provide a strong foundation for human capital.

Second, if this is politically infeasible, efforts to increase exposure to the educational medium are likely to have high returns in human capital. This might be achieved through adult education campaigns in the official language, with the expectation that this would lead to increased use of the language in student homes. Or governments could work to upgrade teacher fluency in the official language, thereby providing better models to their students of its standard use. Whatever the route, the data from our research suggests that future work in development should place more attention on mitigating the high costs of inefficient language policies in postcolonial states for human development.

Authors

David D. Laitin is the Watkins Professor of Political Science at Stanford University.

Rajesh Ramachandran is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics, School of Business at Monash University Malaysia.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/732951

.