Foreign interference in democratic elections has become a source of growing concern. Because outside involvement can affect the outcome of elections, candidates may be tempted to seek foreign help. But foreign meddling can also undermine democracy by eroding public trust in elections and deepening political polarization. Would voters punish candidates who seek foreign electoral support, discouraging politicians from crossing that line?

To find out, we fielded a series of experiments that revealed whether—and under what conditions—U.S. voters would punish candidates for soliciting foreign help during an election.

Our findings offer a mixed message. The vast majority of voters would condone foreign outreach by a candidate from their preferred party. But a small, politically significant group would punish such behavior. Their willingness to defect may help enforce a critical democratic norm: that voters, not foreign powers, should decide elections.

Our Research Design

To explore how U.S. voters react when candidates seek electoral help from foreign powers, we ran a series of large-scale experiments embedded in a nationally representative survey of American adults in 2023. The experiments allowed us to isolate the effects of soliciting foreign involvement while holding all other factors constant.

Participants read scenarios where a presidential candidate reached out to a foreign country—sometimes an ally, sometimes a nonally—asking for help such as endorsements, political ads, or investigations into their opponent. In some cases, the candidate promised something in return (a quid pro quo), such as a trade deal or diplomatic visit, but in other cases, they merely asked for help. In some vignettes, party leaders defended the behavior or cast doubt on whether it had happened, followed by counter-rhetoric by the opposing side. We compared support for candidates in each of these vignettes to baseline support for the same candidates when soliciting was not mentioned.

Most Voters Stayed Loyal When Their Own Party’s Candidate Solicited

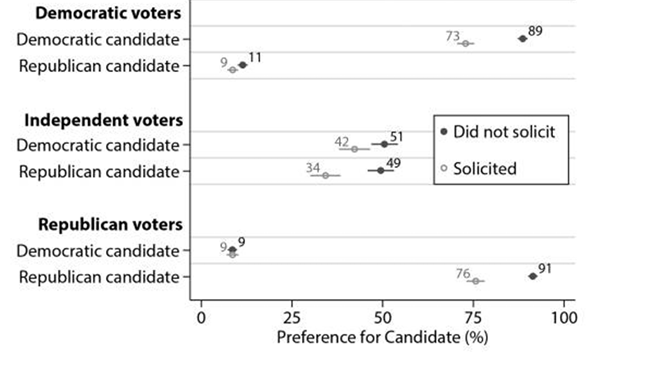

The results were, in many respects, troubling. As Figure 1 shows, the vast majority of voters stuck with their own party’s candidate, even when there was no doubt the candidate had solicited foreign interference. Specifically, 73 percent of Democratic voters and 76 percent of Republican voters continued to prefer their own party’s candidate despite knowing with certainty that the candidate had tried to recruit foreign help.

Figure 1: Preference for Candidate, by Behavior of the Candidate and by Party

Note: The Figure shows results from the Pure Solicitation experiment, in which the candidate had requested help from a foreign country, without any uncertainty about what occurred or rhetoric from political elites.

This was true not only for Republican voters but also for Democrats, despite their outrage after Trump’s 2019 call to Ukraine. Many Americans seem willing to overlook foreign outreach if it serves their partisan goals.

The results also show how soliciting—and perhaps norm violations more broadly—can sow domestic discord. Voters judged episodes of soliciting by the other party much more harshly than the same behavior by their own party’s candidate. Such partisan double standards mean that even clear-cut violations may not generate consensus, making bipartisan accountability more elusive.

Some Episodes of Soliciting Produced Less Punishment

Our study also revealed that not all episodes of soliciting are treated equally.

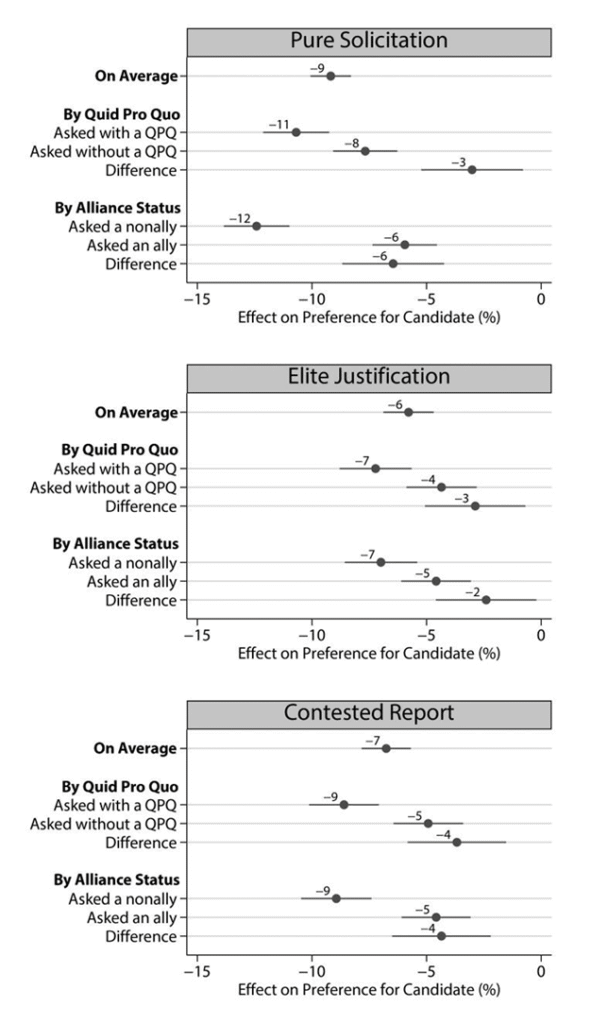

Figure 2 shows that approaching allies like Canada or the UK triggered less backlash than soliciting help from nonallies such as China or Russia. Moreover, candidates who made requests without a quid pro quo were punished less than candidates who promised policy favors in return for election help. Finally, elite justifications (second graph in Figure 2) and contestation about what happened (third graph) blunted the punishments, compared to scenarios without rhetoric and uncertainty (top graph).

Figure 2: Effect of Soliciting on Preference for Candidate

We conclude that some episodes of soliciting are less likely to draw voter rebuke than others. Candidates could minimize electoral backlash by directing their requests toward foreign allies, avoiding the appearance of an explicit quid pro quo, recruiting friendly elites to defend them at home, or playing up uncertainty about what had transpired. By adopting these strategies, candidates could reap the benefits of foreign electoral assistance while minimizing the potential costs.

A Silver Lining?

Nevertheless, in our experiments, a small group of voters punished candidates who solicited foreign help. They withdrew support because they perceived candidates who solicit as less ethical, less competent, and less aligned with their policy preferences, especially when the request was toward a hostile foreign power or the candidate promised something in return.

Punishment did not come from members of the opposite party, who were generally unwilling to vote for an out-party candidate, regardless of whether the candidate had solicited or not. Punishment instead came from moderate (swing) voters and from members of the candidate’s party who found soliciting foreign help odious enough that they were willing to break partisan ranks.

The size of these defections, though small in absolute terms, could be large enough to swing an election. In sum, while most voters condoned their candidate soliciting, a potentially decisive minority was willing to draw the line. In an age of increasing cynicism about the public’s commitment to democratic norms, our study suggests that at least some of the time, a politically consequential minority of voters could help defend democracy by turning against candidates who invite foreign meddling.

Opportunities for Future Research

Our findings open the door to important new questions. For example, why are American voters so tolerant of candidates who seek foreign help? Did they hold those views before high-profile episodes like Trump’s outreach to Ukraine, or did partisan messages shape their reactions afterward? Understanding how these attitudes formed could help reveal ways to strengthen democratic norms.

Future research could also explore whether tolerance for soliciting depends on the intent or context. For example, voters might be more forgiving if a “pro-democracy” candidate sought foreign help to stop an antidemocratic rival. In some cases, voters might welcome soliciting as an attempt to save democracy.

In addition, though our study focused on foreign interference, soliciting is just one of many ways candidates might violate democratic principles. Future research could compare our results to how the public reacts when candidates push for partisan gerrymandering, restrict voting access, or attack the free press.

Finally, while our study focused on the United States, it is important to know how voters in other countries would respond if candidates or parties tried to recruit foreign help to win an election. Are Americans uniquely tolerant because of polarization, or would citizens in other democracies react similarly? Exploring these dynamics across countries could help explain how different societies protect—or erode—their electoral integrity.

Michael Tomz is the William Bennett Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University and a Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Jessica L. P. Weeks is Professor of Political Science and H. Douglas Weaver Chair in Diplomacy and International Relations in the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.