When Politics Meets Government Spending

You might picture debates, elections, or heated headlines when you think of politics. But politics also shapes how the U.S. government buys things—from office supplies to military gear. That’s not just a back-office detail; federal procurement accounts for over $600 billion yearly, roughly 3% of the U.S. economy.

So, who gets those contracts, and how are those decisions made? My research shows that certain political pressures can improve how federal agencies spend your tax dollars.

Powerful Presidents, Unchecked Spending?

Critics have long worried that presidents reward political allies with lucrative, no-bid government contracts, especially under a unified government when their party controls Congress and the White House. Without opposition oversight, watchdogs fear that career officials may face pressure to award contracts to firms tied to the president or their party.

These concerns aren’t just theoretical—they’ve sparked major headlines across administrations, right and left.

- Under President George W. Bush, Halliburton—formerly led by Vice President Dick Cheney—received billions in no-bid contracts during the Iraq War, prompting accusations of war profiteering and political favoritism.

- The first Trump administration also faced backlash during the COVID-19 pandemic. One major controversy involved a $646 million ventilator contract awarded to Philips, a company whose executives and lobbyists had ties to Republican officials. A congressional investigation later concluded that the federal government had overpaid more than $500 million.

- The Biden administration faced scrutiny for awarding an $87 million no-bid contract to Family Endeavors, a nonprofit that had recently hired a former Biden transition official.

These stories trigger public outrage by suggesting favoritism, inefficiency, and a government that rewards insiders.

A Twist in the Tale: When the Opposition Looms

But here’s the twist: our separation of power systems can ensure that federal agencies make better spending decisions even under a unified government.

My research finds that when federal agencies anticipate the president’s party might lose control of Congress, they become more cautious. Agencies then begin awarding more contracts through open, competitive bidding, lowering costs and widening access for firms.

If the opposition wins, it could investigate spending, hold hearings, or embarrass officials. Agencies anticipate this and clean up their act in advance, even when the unified government is still in charge.

Congress’s Power Over Agencies

Given my argument, you might wonder how big the power of future opposition Congress over agencies will be.

While Congress can’t directly veto agency decisions, it has powerful informal tools: committee hearings, budget directives, and even the threat of public shaming of government officials. Agencies know that if they act recklessly now, they might face tough questions—or lose funding or their reputation—later.

So even though Congress’s influence isn’t always written into law, it’s real. And agencies pay attention.

Prediction Markets as Political Thermometers

To empirically test my argument, I needed to know the extent to which agencies perceived a congressional flip might happen. That’s where prediction markets come in.

If you’ve ever placed a bet on a sports game or followed the stock market, you already get the basic idea. A prediction market is like a stock exchange for political outcomes. People buy and sell “shares” in a particular outcome—the incumbent party losing control of the Senate—based on how likely they think it will happen.

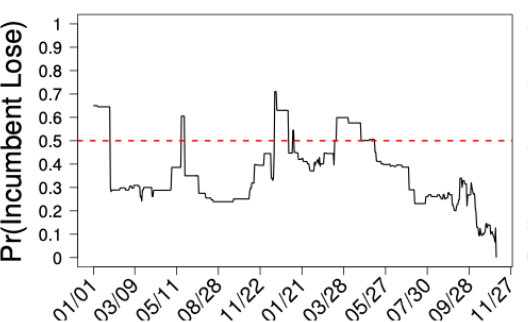

So, if shares are trading at 70 cents, traders believe there’s about a 70% chance the incumbent will lose. If it drops to 40 cents, the perceived probability has fallen to 40%. An example below illustrates the likelihood of congressional turnover for the 2018 Senate election based on daily changes in the Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) prices during 2017-2018. It shows that the likelihood fluctuated substantially until a few months before the election.

Because money is at stake, prediction markets are often accurate. However, the key insight isn’t their precision—the public perceptions they reflect align with how federal agencies gauge the likelihood of congressional turnover. Even if the election is months away, career bureaucrats and political appointees would be tracking the same information that savvy investors in prediction markets are. They know that if the opposition party is gaining ground in the polls—or, in this case, in the prediction markets—then change may be coming. And that change could bring scrutiny, hearings, or even canceled contracts.

What the Data Says

Based on this intuition, I analyzed election prediction markets and federal procurement data from three periods of unified government: the Bush (2005–2006), Obama (2009–2010), and Trump (2017–2018) administrations. Then I looked at how agencies’ day-to-day contracting behavior shifts in response to daily changes in election prediction markets.

Here’s what I found:

- When the probability of congressional turnover in the upcoming election rose, so did the likelihood that federal agencies engaged in competitive contracting.

- This effect was strongest when agencies procured from industries where politically connected firms were numerous and inefficient.

That last point is key: agencies are especially cautious when they know the president’s donor firms are likely to lose in a fair fight in the competitive bidding process, and when a future Congress would smell a rat.

A Note of Caution (and Opportunity)

My findings show that political institutions—like election cycles and separation of powers—can act as built-in checks on favoritism.

This also means we should pay more attention to when and how agencies make decisions, especially in the months before elections.

If you care about government waste—or want to see smarter use of tax dollars—look beyond the campaign ads. The real story might be buried in a contract database.

The Bigger Picture: Bureaucrats as Strategic Actors

This research also highlights a point often overlooked when considering agency spending decisions: bureaucrats, as primary decision-makers of federal contracting, are not merely rule-followers but strategic actors. They read political cues, anticipate future constraints, and adjust their behavior accordingly. This isn’t necessarily bad—in some cases, it can lead to better outcomes.

So next time, if someone tells you the government is always inefficient, ask: Compared to what? And under what conditions?

Because sometimes, the threat of future electoral turnover is exactly what makes bureaucrats act more responsibly.

Authors

Kyuwon Lee